AI Generated Summary

- Stricter student‐visa regulations in Canada, a tightening of enrolment checks in the United States and a temporary suspension of new visas have combined to curb thousands of Indian students’ plans to pursue degrees overseas.

- In a strategic tie‐up with the National Stock Exchange Academy (NSE), GNDU’s University School of Financial Studies will launch an MBA in Financial Analytics and a five‐year integrated M.

- Across Punjab, a remarkable reversal is unfolding in the higher education landscape as shrinking opportunities to study abroad drive a rush of students back to local institutions.

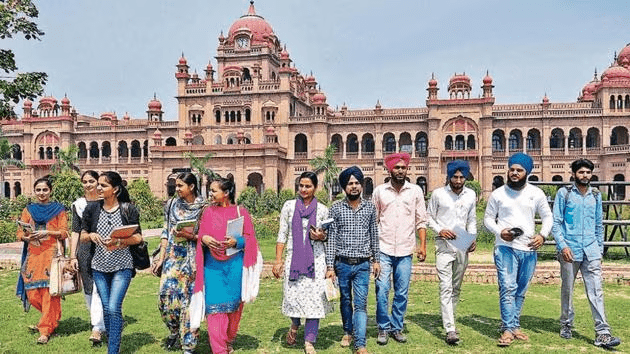

Across Punjab, a remarkable reversal is unfolding in the higher education landscape as shrinking opportunities to study abroad drive a rush of students back to local institutions. Stricter student‐visa regulations in Canada, a tightening of enrolment checks in the United States and a temporary suspension of new visas have combined to curb thousands of Indian students’ plans to pursue degrees overseas. In turn, colleges in cities like Amritsar, Tarn Taran and surrounding rural areas are reporting unprecedented demand for undergraduate seats—breathing life into institutions that only months ago feared closure amid dwindling enrolments.

Visa Crackdowns Abroad Redirect Aspirations to Punjab

Since early 2024, policies in Canada and the US have slowed the issuance of study permits, leaving many aspirants scrambling for alternatives. For years, Punjab families viewed a foreign degree—especially from North America—as the pinnacle of opportunity. But as these doors swing shut, local colleges are suddenly experiencing a windfall. Private institutions that once struggled to fill classrooms are now debating how to accommodate hundreds of new applications.

College administrators across Amritsar and Tarn Taran report an avalanche of inquiries as soon as the Centralised Admission Portal opened earlier this month. After years without formal cutoffs, many colleges have reinstated minimum‐marks thresholds to manage volume. At Khalsa College in Amritsar, the registrar’s office estimates a 40 percent rise in undergraduate applications compared to last year.

“The increase in enrolments is tremendous. While it’s encouraging, it brings its own set of challenges,” said Prof. Davinder Singh, Registrar of Khalsa College. “This year, we have set a minimum cutoff of 60 percent for admissions. The merit of students is quite good, especially in science and computer‐related courses, where we are seeing applicants with scores of 90 percent and above. Given the high number of enrolments, we are also offering specialized diplomas to broaden students’ options.”

Colleges have scrambled to set up help desks across campus to guide applicants through the online portal, a step few had anticipated until recently. By reintroducing admission cutoffs—some as high as 75 percent for B.Sc. (Hons.) programs—institutions hope to strike a balance between preserving teaching quality and absorbing increased demand.

GNDU Unveils Aggressive Expansion Plan

At Guru Nanak Dev University (GNDU) in Amritsar, administrators view the surge as an opportunity to diversify academic offerings. Last week, GNDU released its academic expansion blueprint, unveiling 53 new courses across multiple disciplines. Highlights include:

- Architecture: A four‐year B.Arch. curriculum with upgraded design studios.

- Botanical and Environmental Sciences: M.Sc. programs emphasizing local ecology and sustainable farming techniques.

- Computer Science: B.Tech. and B.Sc. streams incorporating AI, machine learning and cybersecurity modules.

- Hindi Department: A Postgraduate Diploma in Hindi Journalism, plus certificate courses in Hindi Translation and Creative Writing.

In a strategic tie‐up with the National Stock Exchange Academy (NSE), GNDU’s University School of Financial Studies will launch an MBA in Financial Analytics and a five‐year integrated M.Com. in Data Analytics—programs it hopes will attract students keen on careers in fintech and capital markets. University officials believe this expansion not only meets rising demand but also aligns with Punjab’s long‐term goal of nurturing a skilled workforce attuned to emerging industries.

Rural Colleges Confront Resource Crunch

While city‐based colleges in Amritsar are relatively well‐positioned to ramp up faculty recruitment and classroom upgrades, smaller colleges in Tarn Taran and neighboring border villages face tougher odds. Guru Gobind Singh Khalsa College in Sarhali, Tarn Taran, is one such example. Though it received government aid for 22 faculty positions under the grant‐in‐aid scheme, only four posts are currently filled. To cope with the surge, administrators have hired 16 additional teachers on a self‐financed basis—stretching an already strained budget.

“The college is government‐aided, but grant crunch and faculty shortage are hurdles we must overcome before the July admission rush,” explained Dr. Jasbir Singh, Principal of Guru Gobind Singh Khalsa College. “Most students from rural border areas prefer to apply late. We tried increasing approved seats in a few courses, but the conditions imposed by affiliating bodies are strict and financially straining for colleges in this region.”

Two years ago, Dr. Singh recalls, the college was operating at barely half its approved capacity. Today, administrators expect to fill all undergraduate seats, including new batch sizes in B.A., B.Sc. and B.Com. programs. Classroom space is already stretched; labs for science streams are being retrofitted to serve dual purposes, and the library has extended its hours to accommodate additional students.

Infrastructure Upgrades and Faculty Hiring

Across private and affiliated colleges, the pressure to beef up infrastructure is palpable. Some institutions in Tarn Taran have begun minor renovations—converting old storerooms into tutorial spaces and upgrading basic computer labs. However, many lack the funds for large‐scale projects such as expanding dormitories or constructing new lecture halls.

To address long‐term staffing needs, several colleges are negotiating with the state higher‐education department to expedite the approval of new faculty positions. In the interim, they depend on part‐time and guest lecturers. While this approach may be sustainable for humanities and commerce courses, science and computer science streams require specialized faculty and well‐equipped laboratories—resources that are more costly to procure.

Student Perspective: A New Local Option

For students like Priya Sharma, who had her heart set on studying biotechnology in Canada, the shift has been bittersweet. “I was shortlisted by a Canadian university, but my visa was delayed,” she said. “When I saw Khalsa College’s new B.Sc. (Hons.) program with a 65 percent cutoff, I decided to enroll here instead. The campus facilities are good, and the professors seem committed. I feel fortunate to find an alternative close to home.”

Similarly, Harpreet Singh, who hoped to join an MBA program in the US, is now eyeing GNDU’s new MBA in Financial Analytics. “The idea of studying finance with data analytics at GNDU, especially in collaboration with NSE, is attractive,” he noted. “It’s a chance to build industry‐relevant skills without leaving India.”

Looking Ahead

Punjab’s college administrators are optimistic that the current boom in enrolments will help stabilize finances and ward off the threat of closures that loomed over private institutions just a year ago. Yet the sudden influx also raises questions about sustainability: Can these colleges maintain educational quality amid rapid expansion? Will state and university bodies supply adequate support to rural colleges facing acute resource constraints?

For now, local institutions are racing against the clock. With admissions wrapping up by mid‐July, the next few weeks will determine whether Punjab’s higher education ecosystem can transform these visa‐driven disruptions into a lasting advantage for students and colleges alike.