AI Generated Summary

- Titled “A Cultural Study of Transformation of Folk Occupations of Punjab”, the research, spearheaded by Gurjant Singh under the mentorship of Professor Jagtar Singh Joga, explores the declining interest among Punjab’s youth in inheriting ancestral trades.

- A recent study by the Department of Punjabi at Punjabi University has unveiled significant shifts in the traditional occupational landscape of Punjab, highlighting profound cultural and economic repercussions.

- The potter’s son chose a career as a security guard instead of continuing the family’s craft, reflecting the broader trend of youth abandoning their heritage.

A recent study by the Department of Punjabi at Punjabi University has unveiled significant shifts in the traditional occupational landscape of Punjab, highlighting profound cultural and economic repercussions.

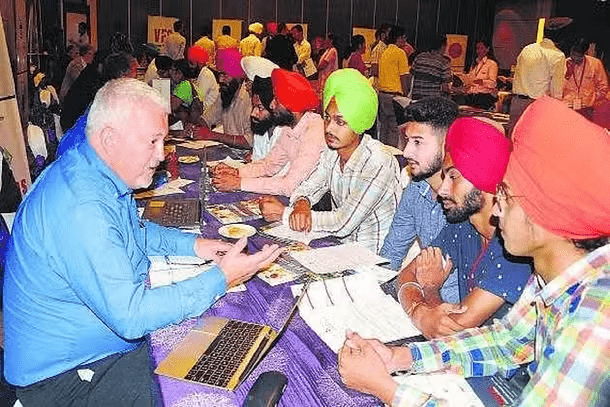

Titled “A Cultural Study of Transformation of Folk Occupations of Punjab”, the research, spearheaded by Gurjant Singh under the mentorship of Professor Jagtar Singh Joga, explores the declining interest among Punjab’s youth in inheriting ancestral trades. This trend is contributing to a surge in unskilled labor and prompting many young Punjabis to seek opportunities overseas.

The comprehensive study examined the lives of artisans engaged in time-honored professions such as agriculture, carpentry, blacksmithing, pottery, goldsmithing, shoemaking, weaving, and tailoring. Through dialogues with 100 artisans, interviews with 66 trade professionals, and an analysis of 135 literary and cultural texts, the research paints a concerning picture of changing priorities among the younger generation.

“Children of artisans are increasingly opting for roles like auto-rickshaw drivers or security guards, perceiving these jobs as more socially respectable,” explained Gurjant Singh. “Families with landholdings are often forced to take loans or sell their land to fund their children’s migration abroad in search of better economic opportunities.”

The decline in traditional occupations is attributed to several factors, including the rise of mechanization, inadequate marketing strategies, and a lack of sufficient government support. While mechanization has introduced advanced tools and techniques, it has also disrupted the cultural fabric, diminishing the interdependence that once characterized these trades.

“Technological advancements have not only changed the tools used but have also reshaped Punjab’s cultural identity,” Singh noted. “The evolution of everyday objects, lifestyles, and cultural expressions has weakened the bonds that once held communities together.”

Another critical finding of the study is the reliance on migrant laborers to sustain traditional trades. “In areas like agriculture and shoemaking, we have become entirely dependent on migrant workers,” Singh stated, highlighting the vulnerability this dependence creates.

A poignant example of this decline was observed in Hadiana village, where a potter’s broken wheel serves as a symbol of fading traditions. The potter’s son chose a career as a security guard instead of continuing the family’s craft, reflecting the broader trend of youth abandoning their heritage.

However, there is a silver lining. In metropolitan areas, traditional pottery and other crafts are experiencing a resurgence, with artisans achieving financial success and renewed appreciation for their work. This urban revival underscores the enduring cultural value of Punjab’s traditional trades.

Despite their dwindling numbers, these occupations remain integral to Punjab’s cultural heritage. Their eco-friendly methods and human-centric approach starkly contrast with the capital-driven nature of contemporary industries. Dr. Jagtar Singh, head of the Department of Punjabi, emphasized the importance of preserving these traditional skills. “If Europeans can restore their traditional crafts, why can’t we?” he questioned, urging for concerted efforts to safeguard Punjab’s rich cultural legacy.

As Punjab stands at this critical juncture, the need to balance modernization with cultural preservation has never been more urgent. Ensuring that traditional trades continue to thrive could not only preserve the region’s heritage but also provide sustainable economic opportunities for future generations.