AI Generated Summary

- From the wooden Persian wheels and bullock-driven ploughs to the intricate bronze utensils and traditional embroidery, the landscape of rural Punjab was evolving at an unprecedented pace.

- Fifty years later, his vision has materialized in the form of the Museum of Social History of Punjab, located on the PAU campus in Ludhiana.

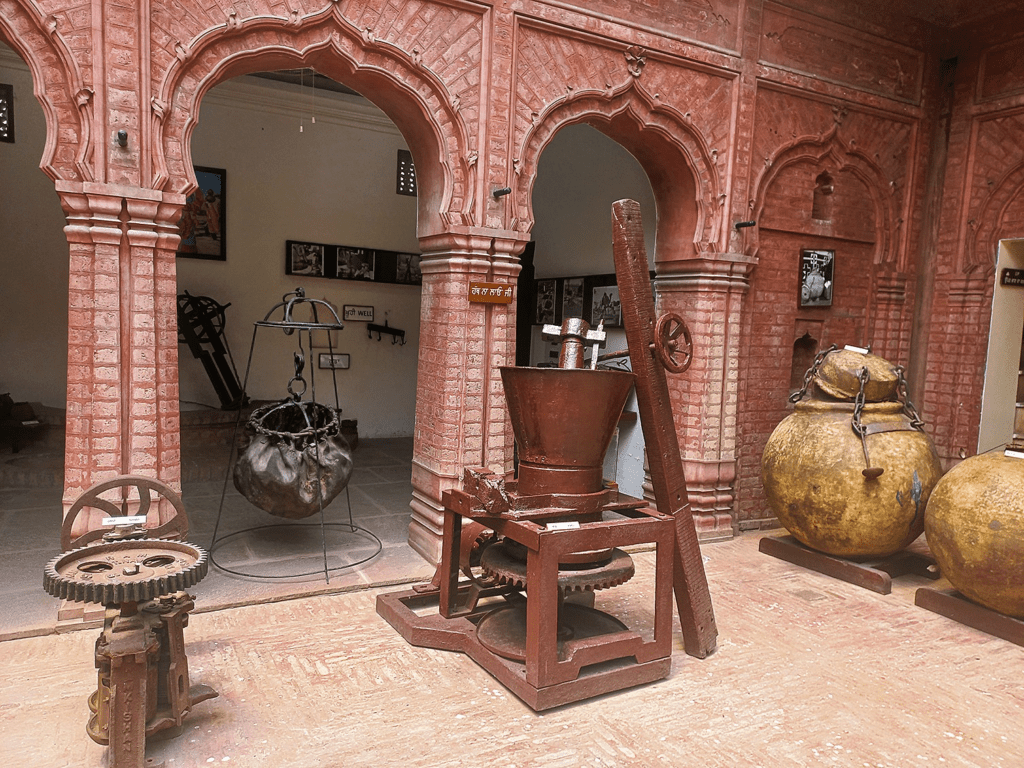

- An 18th-century haveli in Rahon inspired the museum’s design, thanks to the efforts of young architect Surinder Singh Sekhon, who was just 24 at the time.

As the summer of 1970 drew to a close, Dr. M.S. Randhawa, the inaugural Vice-Chancellor of Punjab Agricultural University (PAU), found himself reflecting on a dramatic transformation sweeping through rural Punjab. During one of his routine campus strolls, Dr. Randhawa encountered students from the Home Science College enjoying cold drinks. In an attempt to connect with the younger generation, he asked if they ever drank lassi from traditional brass glasses. The puzzled look on their faces underscored the rapid cultural shifts occurring around them.

Dr. Randhawa observed that the advent of the Green Revolution had ushered in a wave of change, sweeping away traditional practices and artifacts. From the wooden Persian wheels and bullock-driven ploughs to the intricate bronze utensils and traditional embroidery, the landscape of rural Punjab was evolving at an unprecedented pace. Determined to preserve the vanishing heritage, Dr. Randhawa envisioned a museum that would safeguard this cultural legacy.

Fifty years later, his vision has materialized in the form of the Museum of Social History of Punjab, located on the PAU campus in Ludhiana. Inaugurated by renowned author Khushwant Singh in April 1974, the museum stands as a tribute to Dr. Randhawa’s foresight and dedication.

Art historian Kanwarjit Singh Kang, in a 1986 edition of Roop-Lekha, praised the museum’s design, highlighting its foundation in vernacular architecture. Dr. Randhawa’s meticulous approach included visits to historical towns across Punjab, such as Sultanpur Lodhi and Bhadaur, to study and replicate traditional architectural elements. An 18th-century haveli in Rahon inspired the museum’s design, thanks to the efforts of young architect Surinder Singh Sekhon, who was just 24 at the time.

While the museum’s building itself is a replica, its exhibits are genuine artifacts, many over a century old. PAU employees, along with local villagers, were enlisted to gather items representing the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These included musical instruments, traditional attire, phulkaris (embroidered textiles), agricultural tools, and various household items. The museum’s collection also features architectural treasures, such as intricately carved wooden doors and painted ceilings, sourced from historic sites across Punjab.

Dr. Randhawa’s hands-on approach to the museum’s development was evident in his frequent visits to the construction site. His dedication extended to sourcing artifacts and encouraging donations. For instance, he persuaded Dr. B.P. Pal, the first Director General of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, to donate a collection of phulkaris, which were later named in honor of Pal’s sister.

By the time the museum opened its doors on November 30, 1973, it had garnered substantial support from friends, civil servants, and the public. One notable contribution came from bureaucrat M.S. Gill, who spotted a Persian wheel on his travels and recommended its donation to the museum.

Dr. Randhawa’s dual objective for the museum was to conserve Punjab’s rapidly disappearing heritage and integrate it into educational experiences for students. His vision was to provide a holistic education that encompassed both scientific knowledge and cultural heritage.

Today, the Museum of Social History of Punjab attracts thousands of visitors annually. With over 69,000 visitors up to June this year alone, it continues to fulfill Dr. Randhawa’s vision of preserving and celebrating Punjab’s rich cultural past. As visitors explore the museum’s exhibits, they encounter a tangible connection to a bygone era, reflecting the enduring impact of Dr. Randhawa’s dedication and foresight.