AI Generated Summary

- Banga’s visit, part personal pilgrimage, part diplomatic mission, offered a golden opportunity to project an image of tolerance to a powerful figure of Sikh heritage, whose endorsement could soften perceptions in Western capitals and among influential diaspora communities.

- Ajay Banga’s gracious visit and praise may have been well-intentioned, but the backdrop tells a different story, one of a state that restores a gurdwara not for devotion, but for dollars.

- It was not driven by la ongstanding commitment to minority rights but by the need to “whitewash” a grim record ahead of scrutiny from someone whose background and influence could amplify criticism.

The restoration of Gurdwara Singh Sabha in Khushab, Pakistan, just days before World Bank President Ajay Banga’s visit to his ancestral hometown, was no coincidence. It was a calculated performance, one that exposes the Pakistani state’s cynical use of minority heritage sites as props in its desperate bid for international legitimacy and financial lifelines.

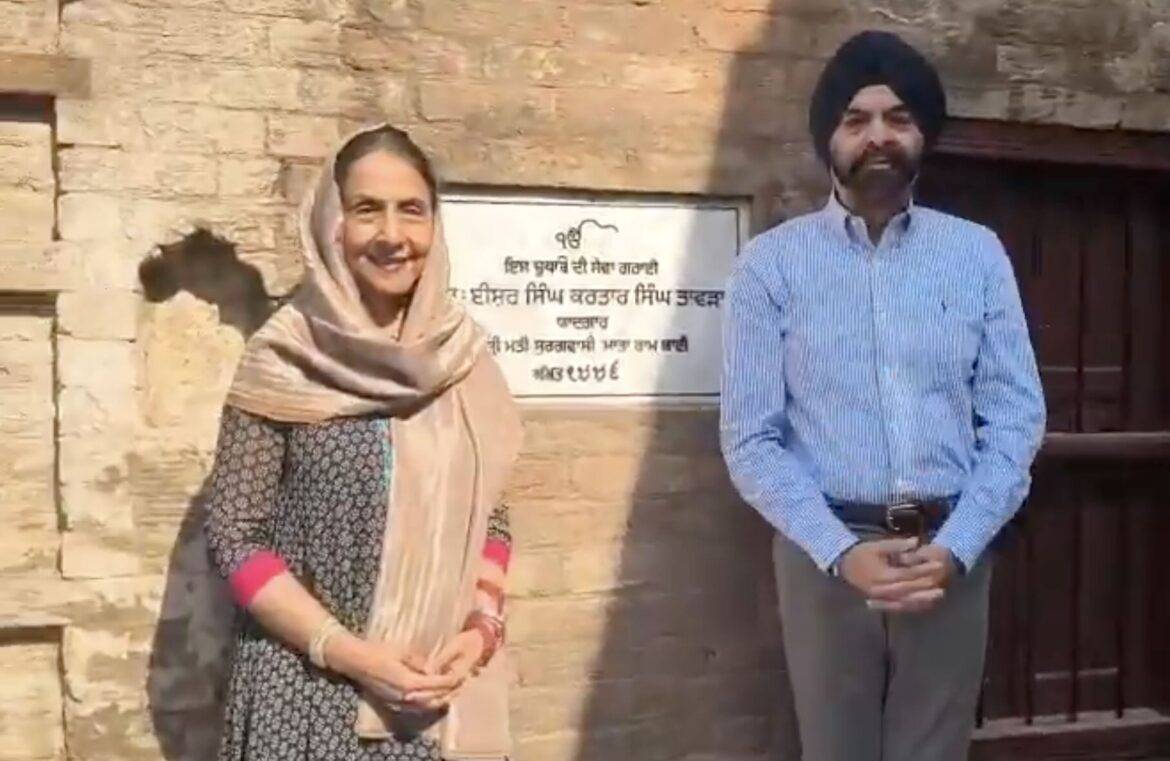

Managed by the Evacuee Trust Property Board (ETPB), the gurdwara had languished in dilapidated condition for years, like so many other Sikh shrines and minority religious sites across Pakistan. Despite being under official jurisdiction, it received little meaningful attention—until the timing aligned perfectly with Banga’s high-profile trip in early February 2026. Restoration work began abruptly, with Punjab government involvement, creating a polished facade for the visiting dignitary. Banga, whose family roots trace back to Khushab, paid homage at the site, examined ancestral records, and publicly commended the “development and administrative measures” undertaken there. Pakistani officials highlighted the efforts as evidence of interfaith harmony and heritage preservation.

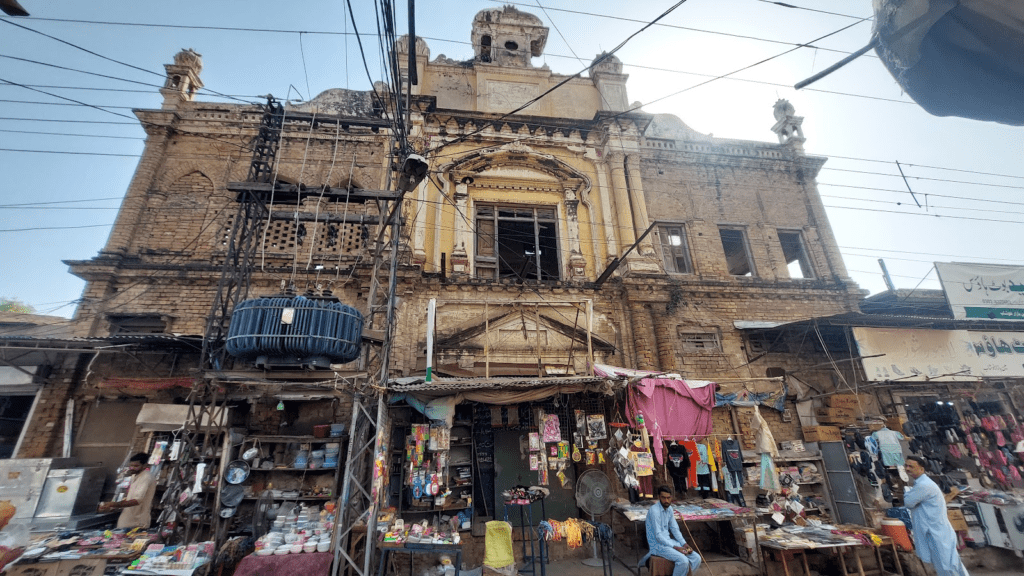

This sudden burst of activity raises uncomfortable questions: Why prioritize a relatively lesser-known gurdwara when countless other Sikh, Hindu, and Christian sites of greater historical and religious significance remain neglected, vandalized, or in ruins? The answer lies not in genuine concern for minority rights, but in Pakistan’s precarious economic reality. The country teeters on the edge of collapse, burdened by debt, inflation, and military expenditures that devour resources. Securing fresh loans and aid from institutions like the World Bank is existential. Banga’s visit, part personal pilgrimage, part diplomatic mission, offered a golden opportunity to project an image of tolerance to a powerful figure of Sikh heritage, whose endorsement could soften perceptions in Western capitals and among influential diaspora communities.

The optics were carefully curated: Banga praised the ETPB’s work, posed for photographs at the restored shrine, and spoke positively about Pakistan’s commitment to Sikh pilgrims. Yet this stands in stark contrast to the lived reality of religious minorities in Pakistan. Christians and Sikhs face persistent systemic persecution, blasphemy laws weaponized to settle scores, mob violence often ignored or abetted by authorities, forced conversions (especially of young women), targeted abductions, and destruction of places of worship. Reports from bodies like the USCIRF and human rights organizations document a pattern of intolerance: churches burned, communities terrorized, and minorities marginalized in jobs, education, and justice. Sikhs, in particular, endure abductions and violence in regions like Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, while their heritage sites are frequently allowed to decay until a spotlight shines.

Restoration of historic Gurdwara Guru Sangh Sabha, Khushab, in progress ❤️ pic.twitter.com/1Bfb0D7J2a

— Maryam Nawaz Sharif (@MaryamNSharif) January 27, 2026

The timing of the Khushab restoration reeks of opportunism. It was not driven by la ongstanding commitment to minority rights but by the need to “whitewash” a grim record ahead of scrutiny from someone whose background and influence could amplify criticism. Pakistan’s government has long used selective gestures, opening a shrine here, facilitating a pilgrimage there, to deflect attention from broader failures. When minorities suffer routine discrimination, violence, and erasure, a last-minute paint job and photo-op do not constitute progress; they constitute propaganda.

True respect for religious heritage would mean consistent protection, not cosmetic fixes timed to impress visitors. It would involve dismantling discriminatory laws, prosecuting perpetrators of violence against minorities, and ensuring equal rights rather than performative displays. Until then, such gestures remain what they are: transparent attempts to secure loans and legitimacy while the underlying oppression continues unchecked.

The world should not be fooled. Ajay Banga’s gracious visit and praise may have been well-intentioned, but the backdrop tells a different story, one of a state that restores a gurdwara not for devotion, but for dollars. Minorities in Pakistan deserve far more than a hastily staged showcase; they deserve justice, safety, and dignity every day, not just when a powerful guest comes calling.