AI Generated Summary

- This unease is rooted in a predominantly Hobbesian understanding of society and international relations, which emphasizes human selfishness and the necessity of a balance of power.

- In this view, a multipolar world is inherently chaotic and unstable, as alliances are prone to frequent and unpredictable shifts based on the changing interests of major powers.

- This perspective is reminiscent of the pre-World War I and inter-war periods, where the lack of a dominant power led to instability and conflict.

The discourse surrounding the global strategic community today often hinges on whether a multipolar world order is advantageous or detrimental. Many Western scholars and politicians seem particularly perturbed by the concept of multipolarity, often favoring a unipolar or bipolar world dominated by clear hegemons. This unease is rooted in a predominantly Hobbesian understanding of society and international relations, which emphasizes human selfishness and the necessity of a balance of power.

The realist school of international relations, which dominates Western thought, posits that humans are fundamentally self-interested and that international relations are characterized by a constant struggle for power. In this view, a multipolar world is inherently chaotic and unstable, as alliances are prone to frequent and unpredictable shifts based on the changing interests of major powers. This perspective is reminiscent of the pre-World War I and inter-war periods, where the lack of a dominant power led to instability and conflict.

Contrastingly, India’s strategic thought, deeply rooted in its metaphysical and epistemological traditions, presents a different understanding of human nature and international relations. Indian philosophical thought, which considers reality to be Trigunatmak—a blend of three attributes: Sat (selflessness and piety), Rajas (activity and movement), and Tamas (darkness and lethargy)—suggests that human nature is a dynamic combination of these attributes. Consequently, human behavior is not purely selfish or selfless, violent or peaceful, but rather a complex interplay of these tendencies.

From this perspective, the Indian worldview rejects the notion that war and conflict are the inevitable outcomes of human interaction. Instead, it views multipolarity as a natural and desirable condition of the international order. In a multipolar world, multiple civilizational states coexist as fundamental poles, each embodying its unique values, ethos, and cultural norms. This plurality implies a world where different political systems, including dictatorships and democracies, can coexist, promoting tolerance and diversity.

India’s historical experience with multipolarity dates back to the later Vedic age (900–600 BC), when 16 Mahajanpadas, or great kingdoms, coexisted in the Indian subcontinent. These states, ranging from northern Afghanistan to the borders of Myanmar, included monarchies and republics. The inter-state relations during this period reflect India’s approach to multipolarity, characterized by the principle of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam—the world is one family. Powerful states, like Mathura and Dwarka, were seen as leaders or elders of this global family, expected to exhibit moral behavior and benevolence.

This historical precedent highlights that powerful states were not hegemons or bullies but rather benevolent leaders expected to act in the enlightened self-interest of the entire family of nations. Their role was not to dominate but to ensure a win-win situation for all, maintaining balance and order. This framework allowed for flexibility and moral considerations in inter-state relations, with the ultimate goal being moral or spiritual victory, known as Dhammavijay or Dharmavijay.

In contemporary times, India’s comfort with multipolarity is evident in its independent and principled foreign policy. During the Cold War, India chose a path of non-alignment, refusing to join either the capitalist or communist blocs. This policy was rooted in India’s civilizational alignment with multipolarity. Today, this non-alignment has evolved into a multi-alignment strategy, where India maintains relations with diverse nations, including those in rival camps.

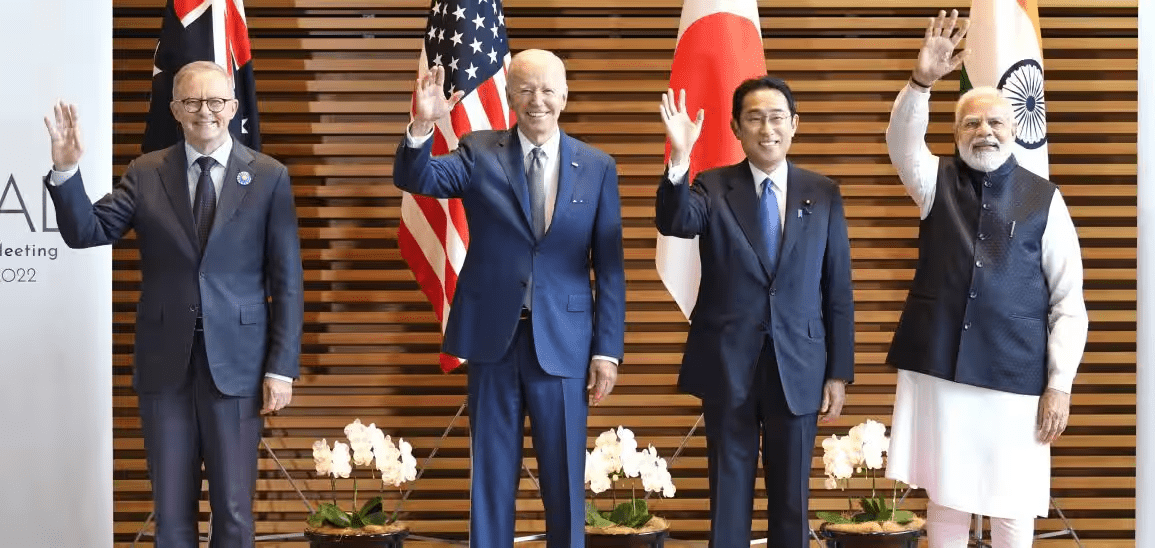

For instance, India has strong ties with both Israel and Iran, and with Saudi Arabia and Iran. It shares a natural partnership with the United States based on shared democratic values, yet it also maintains a ‘special and privileged strategic partnership’ with Russia. Despite border clashes with China, India continues robust trade relations with Beijing. This balanced approach enables India to reject great power politics and advocate for reforms in multilateral institutions to reflect more diversity and inclusive cooperation.

India’s leadership in the Global South, an extension of its non-aligned movement, further demonstrates its commitment to a multipolar world order. Under India’s G20 presidency, the African Union became a full member of the G20, reflecting India’s push for greater representation and inclusivity in global governance.

India’s independent foreign policy has also earned it credibility on the global stage, as evidenced by its stance during the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Despite Western pressure, India refused to join anti-Russia sanctions, positioning itself as a credible mediator. This balanced approach was acknowledged by U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who noted India’s role in deterring Russia from using nuclear weapons.

Thus, multipolarity is not inherently problematic. The current shifts in global politics are steering us towards a multipolar world order, which, if approached constructively, can be beneficial. The United States, often viewing power distribution through a zero-sum lens, could learn from India’s approach to multipolarity. By embracing bilateralism and mini-lateralism, the U.S. can leverage its influence in a multipolar world, promoting development aid, reforming multilateral institutions, and fostering inclusive cooperation.

India’s diplomatic strategies, grounded in its civilizational ethos, offer a valuable template for navigating a multipolar world. This approach emphasizes moral and spiritual power over mere economic and military might, aiming for a world where leaders act as Vishwamitras (friends of the world) and Vishwagurus (teachers of the world), rather than hegemons.

India’s embrace of a multipolar world order with dignity is rooted in its unique philosophical and historical perspectives. By advocating for a pluralistic and inclusive international system, India demonstrates that multipolarity can be a source of stability and cooperation rather than chaos and conflict. As global politics continues to evolve, India’s principled and independent foreign policy offers a model for navigating the complexities of a multipolar world, fostering a global order that is equitable, diverse, and harmonious.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Khalsa Vox or its members.