AI Generated Summary

- On being asked about it, the veteran writer remarked that it was a remnant of the Muslim family residing there before the partition in 1947 and he had retained it as it was, so that if the newer generations of the old owners ever visited from “lahnde Punjab” (Pakistani Punjab), they at least found some vestige of their ancestors.

- There is also a Gurudwara in Khushwant Singh’s neighborhood which is built on what was a mosque’s land till 1947 but the mosque is a part of the Gurudwara even now and the author is in charge of its upkeep.

- In Halwara, a small village in Ludhiana district, Jagjit Singh built a mansion for himself in 2009 but, like Singh, retained a pre-partition ‘haveli’ that belonged to a Muslim Rajput family, saying that “I am a lover of Punjabiyat.

Khushwant Singh’s home near Ludhiana, Punjab, is a contemporary structure, beautifully and aesthetically constructed but it has an odd-looking sitting area in front of it. On being asked about it, the veteran writer remarked that it was a remnant of the Muslim family residing there before the partition in 1947 and he had retained it as it was, so that if the newer generations of the old owners ever visited from “lahnde Punjab” (Pakistani Punjab), they at least found some vestige of their ancestors.

There is also a Gurudwara in Khushwant Singh’s neighborhood which is built on what was a mosque’s land till 1947 but the mosque is a part of the Gurudwara even now and the author is in charge of its upkeep.

In Halwara, a small village in Ludhiana district, Jagjit Singh built a mansion for himself in 2009 but, like Singh, retained a pre-partition ‘haveli’ that belonged to a Muslim Rajput family, saying that “I am a lover of Punjabiyat. I believe that this ‘haveli’ is my inheritance. How can a man part with his inheritance?”

Punjab is the heartland of India. This heartland was cruelly, unthinkingly butchered by the colonial rulers almost 75 years ago, the scars of which cause agony on both sides of the border, even today. There are many instances of such experiences in both Punjabs as they share a common legacy. ‘Punjabiyat’ as it is referred to, means a common cultural identity of the two Punjabs. Not only the language, Punjabi, but even the heroes and folklores remain shared across the borders; folktales like ‘Heer-Ranjha’ are our very own equivalent to ‘Romeo and Juliet’, Guru Nanak Devji is revered by Sikhs and Muslims alike, Waris Shah, Baba Bulle Shah, and Baba Farid are Sufi saints who are respected by both communities alike, not to forget Shaheed Bhagat Singh who is a partition hero in both countries, irrespective of his religion. As an aftermath of partition, this Punjabi identity suffered as the government in Pakistan Punjab did give much stress to the Punjabi language and culture.

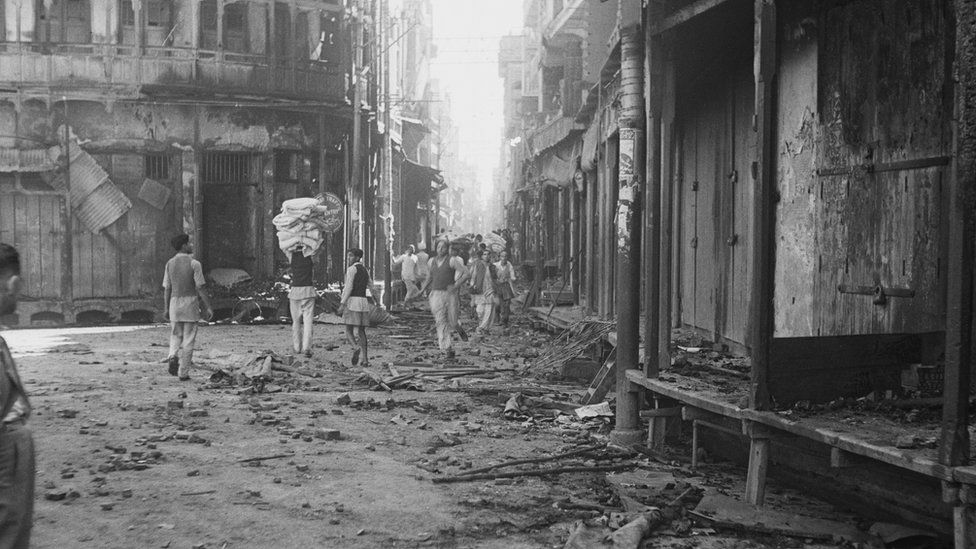

The question here arises, what went wrong as India gained independence? Why did the demarcation of borders let loose such a carnage that there was near total cleansing of minorities on both sides of divided Punjab? The situation was very serious and complex. The British policy of ‘divide and rule’ is undoubtedly to be blamed. However, the political players of both communities accentuated the differences to pave the way to their respective ‘nationalisms’. The brunt of which was born by the common people as torrents of communal violence were unleashed.

The Sikhs of Punjab were worst hit because they were facing the danger of losing everything; their land, valuables, religion, and even their religious shrines. They felt wronged and vulnerable as they feared their revered ‘Gurudwaras’ would be lost forever in Pakistan Punjab and the resistance to this was on a war scale. Sardar Ganga Singh said, “Whatever happens to the other aspects of the division of Punjab, the Sikhs will never tolerate the division of their holy places. We have no hesitation in declaring that Sikhs will be ready to fight once again as they did in the past”.

And while the communal fires continued to be fueled by hatred and insecurity, the British continued to turn a blind eye towards the gravity of the situation. The great exodus began which led to the exchange of over a million people on both sides. If the numbers were not staggering enough, the condition of the refugees was even more pathetic. Men, women, and children defeated, traumatized with their few earthly belongings like cycles, cattle, and charpoys, formed caravan after caravan. There were innumerable people, hungry and broken, passing their ‘once-friends’ with only antipathy and fear rather than camaraderie and hope. It is said that the moment these refugees set foot on Indian soil they heaved sighs of relief and slogans like “Azad Hindustan Zindabad” reverberated in the atmosphere.

Punjab burnt, on both sides of the border. The governments tried to control situations on a massive scale but the numbers were against them. While the leaders of East Punjab tried in vain to discourage the masses from retaliatory activities, they also faced the challenge of rehabilitating and settling the refugees who had nowhere to go. Nothing to do. They had to be fed, safeguarded from diseases, and given aid. A task that seemed daunting. On the other side, however, the Sikhs in East Punjab (Pakistan) still faced an identity crisis. They did not know what fate had in store for them.

If we talk about numbers, it is estimated that the death toll of the partition of India was over six to eight hundred thousand people, while six million Hindus and Sikhs evacuated East Punjab, eight million Muslims moved to East Punjab. Another searing figure that seems unbelievable, yet is shamefully true, is the plight of women – over three hundred thousand were killed, not the mention countless others who faced worse fates by being converted or raped and tortured in the most inhumane ways, irrespective of their religion and region.

How can this barbaric war (yes it was a war!) ever be justified? How could the mighty, flourishing Punjab be reduced to a mere skeleton with its soul being divided by a border? It is said that the foundation of the Golden Temple was laid by the Muslim Fakir, Sain Mujan Mir on the behest of the fourth Guru Ramdas. Muslim pir, Buddhu Shah was a firm devotee of the tenth Guru Gobind Singhji. There are tales of deep friendship between Guru Nanak Devji and Bhai Mardana. The city of Amritsar today stands on land donated by Akbar to the third Sikh Guru Amardas. To date, writers and authors from both countries are taught about in educational institutions across borders.

After so much documented cultural exchange, what caused the discord? What made those friends turn to foes, thirsty for each other’s blood? How could the Muslim brothers rape their Hindu sisters in cold blood? What can ever justify the reasons for a Sikh son who killed his Muslim mother who made ‘sevwiyan’, especially for him every Eid? The ‘Punjabis’, I don’t mean Hindus /Muslims; I mean the people of Punjab, have never looked upon 1947 as the year of independence, on the contrary, Punjabi intellectuals and scholars feel that the wounds of 1947 might have healed with time but the scars will always remain.

Punjabi winters and poets like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Gulzar, and Habib Jalib have written heart-rending pieces about the Punjab partition which reflect the grief and pathos caused by it’s ensuing incidents. Munir Niazi’s poem “Kitthe jaiye” talks poignantly about the division of Punjab.

A Punjabi poet, Ustaad Daman writes about independence and partition,

“Bhavein muhon na kahiye, par vichon vich, khoye tussi vi o, khoye assi vi aan.

Inha azadiyan hathon barbaad hona, hoye tussi vi o, hoye assi vi aan.

Kucch umeed-e-zindagi mil jayegi, moye tussi vi o, moye assi vi aan.

Jyondi jaan ee maut de muh andar, dhoye tussi vi o, dhoye assi vi aan.

Jaagan vaaliyan rajj ke luttiyan e, soye tussi vi o, soye assi vi aan.

Laali akhhiyan di pai dassadi e, roye tussi vi o, roye assi vi aan“.