AI Generated Summary

- Considering that the interest and practice of Guru Nanak were evolving an epistemological cut in the philosophical thinking and religious practice of his times, he avoided portraitures and physical images but ensured the inscription of his ideas in the written form by hand.

- It is here that the universal image needs to be free of a form, a time, and a place even though it has a form in a time and a place.

- Yet, long after he left the world, his followers prepared a kind of primers for preaching the ideas and philosophy of Guru Nanak in the simplest ways.

The Physical appearance of Guru Nanak cannot be truly canonized because no real image from his lifetime for any future facsimile exists, nor should it be canonized because he rejected any unique facial identity of God or a prophet. Moreover, there is always transcendence from specific (individual) to global (universal) for a human born to be godly. The historical real image of a prophet or a thinker has to fade into a universal image. It is here that the universal image needs to be free of a form, a time, and a place even though it has a form in a time and a place.

The evolution of the individual in his philosophy is a process of losing physical identity and gaining intellectual and philosophical identity. Considering that the interest and practice of Guru Nanak were evolving an epistemological cut in the philosophical thinking and religious practice of his times, he avoided portraitures and physical images but ensured the inscription of his ideas in the written form by hand. To look the way others looked, yet think and practice differently from them, he lived among them wearing the dresses of his time but renounced the contemporary ideologies, practices, and rituals. His udasis (travels) were not renunciation of the world and society but his preaching tours through dialogue and discourse. These were neither pilgrimages nor journeys to ‘indifference’ in the literal sense of the word but were a rise from the personal to the universal engaging with people and their wellbeing. That is why he challenged several socially ill practices and religious philosophies of the Power and its relation to humans.

Sikhism is founded on a balance between the binaries of temporal and universal, on the one hand, and material and spiritual, on the other. Thus God is formless. “Thapia na jaye kita na hoye, aape aap niranjan soye”: It cannot be established nor it can be created for it is there by itself. This is how the Super Power is described and this is how, later in the history of knowledge, Matter is described.

If that is so, it is unreasonable to canonize the portraitures of the philosopher Guru who teaches abstaining from idolatry.

The distinctiveness of the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib sanctified as the Shabad Guru, is its genesis directly by its prophets. We can access, understand, and identify ideological Guru Nanak distinct from others, but we cannot identify his phenotype. It is not possible to identify the contours of his face, the shape of his eyes, ears, nose, lips, etc. However close to the real a portraiture, construed from his writings and narratives of his life may be, it will remain imaginary. Then why run against the teachings of the one whom we intend to show reverence by portraying his image?

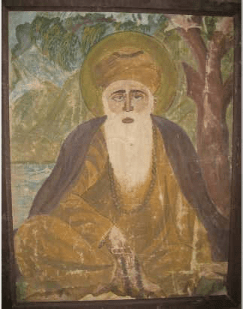

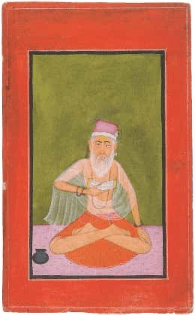

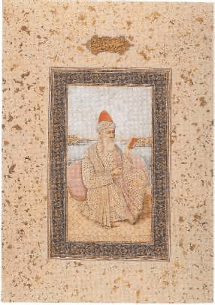

Yet, long after he left the world, his followers prepared a kind of primers for preaching the ideas and philosophy of Guru Nanak in the simplest ways. These are known as Janam Sakhis, the handwritten (manuscripts) describing the events related to his birth, childhood, travels (Udasis), and the final settlement. Later, following the Pahari miniature painting tradition, the paintings were added to the Janam Sakhis as visual illustrations of the narratives. This is how the practice of portraying Guru Nanak was started.

The narratives added mythological elements to history so as to achieve the goal of communicating with the masses of those times in their idiom. In the absence of any authentic portrayal, the portraitures of Guru Nanak depended heavily on the understanding and imagination of the painters. As a result, even in its first stage in the seventeenth century, the images varied. While in some portrayals, Guru Nanak is shown wearing a cap in different styles, in others wearing a turban. In some paintings his head has a circular golden halo, in others it is absent; in some, he has a rosary in the hand, ‘tilak’ on the forehead, in others he has not. In different portraitures, he has different contours of the face. The variation is rather a principle than an exception during the initial period.

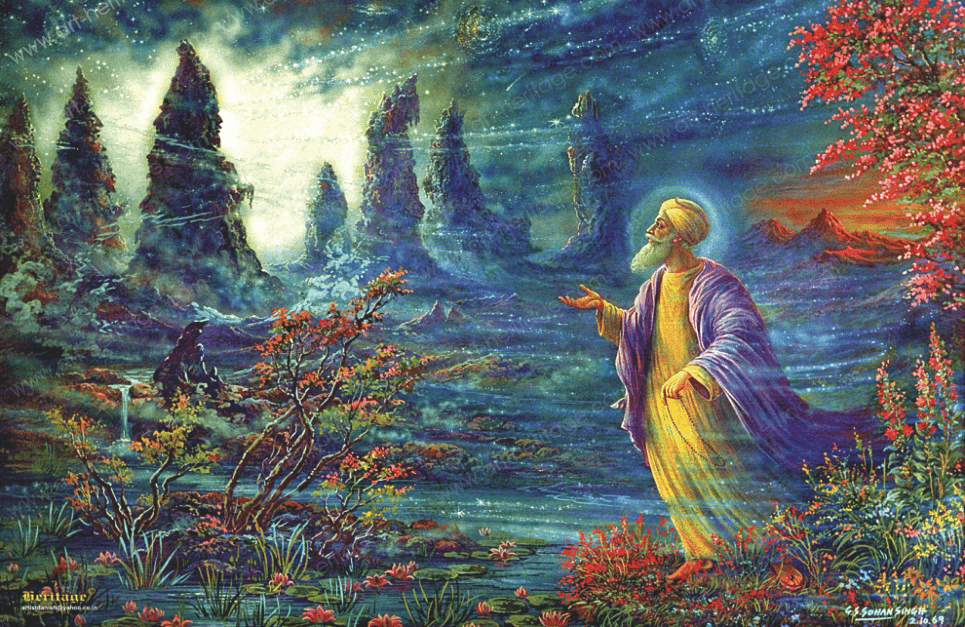

The efforts to create an iconic image of Guru Nanak have been a slow but continuous process: gradually, Guru Nanak is shown in varied sitting or standing poses in the ambiance of beautiful and ethereal elements of nature. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the portraiture of Guru Nanak reveals a departure from the Kangra miniature style and Hindu symbolism of saintliness, wearing a long white beard and a turban on the head. These paintings do not narrate an event but portray a persona of Guru Nanak individually or accompanied by Bala and Mardana highlighting his divine image. Influenced by western techniques including medium, form, and format, according to Kavita Singh, modern artists use the Western style “to project idealism in a realistic manner”.

Such a variation in the portraiture of the great philosopher and the Guru has created controversies more than once in the recent past, such as the use of an image of Guru Nanak in a school textbook in California and his visual portrayal in a film.

To avoid such controversies on the body, dress and his physical postures of sitting or standing, it is possible to avoid portraying to identify or canonise Guru Nanak in physical appearance. Those who want to paint an imaginary image based on the readings of his writings may do that without naming their work as Guru Nanak. However great a painter someone may be, however, a devout follower someone may be, he cannot pay respect to Guru Nanak by acting against his teachings.