AI Generated Summary

- Three years after the government approved a ₹100-crore project to build an 800-metre bridge over the Ravi River, the structure remains trapped in red tape — a stark monument to bureaucratic inertia and political indifference.

- The project was hailed as a game-changer — not just a link to the mainland but a lifeline for thousands.

- For the 3,500 residents of eight hamlets cut off by the river and hemmed in by the Pakistan border, hope has become as distant as the mainland itself.

Three years after the government approved a ₹100-crore project to build an 800-metre bridge over the Ravi River, the structure remains trapped in red tape — a stark monument to bureaucratic inertia and political indifference. For the 3,500 residents of eight hamlets cut off by the river and hemmed in by the Pakistan border, hope has become as distant as the mainland itself.

Locally known as “Us-Paar-Pind” — literally, “villages on the other side” — this cluster of settlements exists in near isolation. The meandering Ravi separates them from the rest of India, leaving their residents dependent on a temporary pontoon bridge that is dismantled each monsoon. For four months each year, they rely on a single rickety boat to cross turbulent waters.

A Forgotten Frontier

The villages, spread over 700 acres, are caught between two perils: an unpredictable river and a volatile international border. During recent hostilities between India and Pakistan, the area was viewed as a tactical weak point — an Achilles’ heel in India’s northern defences. Without a permanent bridge, even troop movement was virtually impossible.

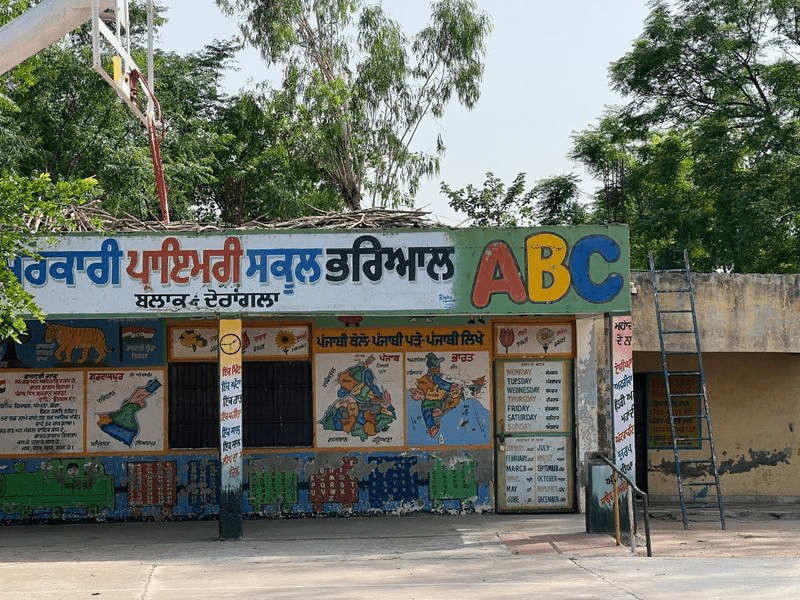

But beyond strategy and security, it’s human lives that have been stranded. The people here live without basic amenities: no potable water, no functioning healthcare, no reliable schools. “We are treated as if we live on another planet,” says Ranjit Singh of Lassian village. “We cannot educate our children or access proper medical care. We are forgotten citizens.”

Promises, Plans, and Paralysis

In August 2021, the Union Government sanctioned ₹100.48 crore for the bridge after the Army granted its no-objection certificate. The project was hailed as a game-changer — not just a link to the mainland but a lifeline for thousands. Yet, three years on, the bridge remains a promise on paper.

The reason? A mere 5.85 acres of land needed for approach roads has yet to be acquired. Officials cite “minor procedural issues.” Villagers call it “criminal neglect.”

Meanwhile, the pontoon bridge remains their only tenuous link. It’s off-limits to tractors carrying produce, forcing farmers to wait for river levels to drop before they can reach markets or sugar mills. Veterinary services are non-existent, and livestock deaths are routine. During monsoons, medical emergencies turn fatal — women have delivered stillborn babies while waiting to cross the flood-swollen river.

The Human Cost of Indifference

Poverty has become generational here. “Ninety percent of girls drop out after middle school,” says Avtar Singh of Toor Chib village. “How can they study when they can’t even cross the river? The government talks of ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao,’ but here, those words mean nothing.”

Marriage prospects, too, are grim. Families across the river are reluctant to marry into “Us-Paar-Pind,” fearing months of separation when the pontoon bridge is removed. “Our girls are trapped,” laments a villager. “Even when they get jobs, they can’t go to work half the year.”

A Bridge Too Far

Since Independence, 11 Members of Parliament have represented Gurdaspur — among them, film star Vinod Khanna and veteran politician Sukhbans Kaur Bhinder. Not one, locals say, has ever set foot across the Ravi. The area’s small population makes it politically inconsequential. “We don’t matter because we don’t count,” says another resident bitterly.

In 2002, MLA Aruna Chaudhary managed to install the first pontoon bridge, a move that earned her enduring respect. But even she could only offer a temporary fix. The permanent bridge, promised two decades later, has become a casualty of the same bureaucratic apathy that defines India’s infrastructure woes.

Waiting for Deliverance

The residents of Us-Paar-Pind continue to live lives defined by uncertainty — their existence shaped by a river’s moods and a system’s indifference. The bridge, if ever completed, could transform their lives, connect them to opportunity, and fortify a vulnerable border.

Until then, they remain marooned — citizens in name, abandoned by progress, waiting for someone in power to finally cross the bridge to their side.