AI Generated Summary

- Its acceptance could have averted the necessity for the controversial section 125 A in the Sikh Gurdwaras Act of 1925, mandating the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) to facilitate free-to-air live telecast of Gurbani.

- From its initial role in controlling Gurdwaras in pre-Independence India to its frontline stance in agitations for Sikh recognition as a religion separate from Hinduism, the SGPC has shaped Sikh representation over time.

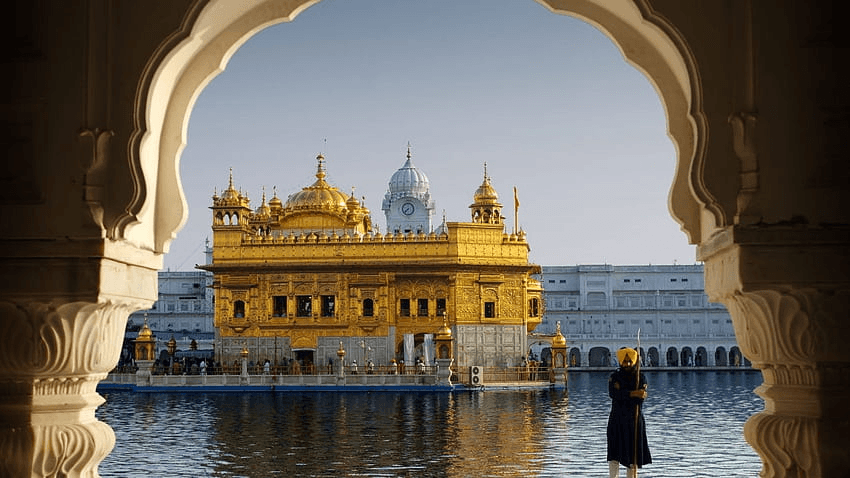

- The Shiromani Akali Dal’s longstanding plea in the tumultuous 1980s for the live broadcast of the Gurbani from Amritsar’s revered Golden Temple via All India Radio (AIR) sheds light on a historical juncture.

The Shiromani Akali Dal’s longstanding plea in the tumultuous 1980s for the live broadcast of the Gurbani from Amritsar’s revered Golden Temple via All India Radio (AIR) sheds light on a historical juncture. It was a demand only acknowledged post-1984’s Operation Blue Star, highlighting a missed opportunity for reconciliatory gestures. Its acceptance could have averted the necessity for the controversial section 125 A in the Sikh Gurdwaras Act of 1925, mandating the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) to facilitate free-to-air live telecast of Gurbani. A demand born out of the intention to challenge the Badal family’s exclusive telecasting rights over the past decade.

The ongoing legal saga, recently stirred up by Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann, hints at a deeper historical context. There’s merit in examining the transitional provisions of the Reorganisation of Punjab Act 1966, and the Narendra Modi government’s application of it in 2016. It excluded Sehajdharis from Sikh Gurdwaras’ electoral college, emphasizing the intermingling of politics with religious representation.

Fast forward to today, the SGPC, first established in 1920, stands as a symbol of Sikh representation, albeit steeped in political undertones. From its initial role in controlling Gurdwaras in pre-Independence India to its frontline stance in agitations for Sikh recognition as a religion separate from Hinduism, the SGPC has shaped Sikh representation over time. However, the control over this institution, with an annual budget of Rs 1,100 crore and oversight of significant Sikh religious sites, breeds power struggles and conflict.

The contested authority and fiscal management within the SGPC mirror a broader reality. Gurdwara elections have fallen by the wayside, the Haryana body remains ‘ad-hoc,’ and questions loom over Sikh representation in regions outside of Punjab. Despite a population of 2 crore Sikhs and countless more Guru Granth Sahib followers in India, the decentralized presence of the Sikh community presents unique challenges for representation.

These complexities are amplified by the Akali Dal’s precarious stance on the All India Gurdwara Act. While seemingly in favor, they simultaneously fear it may weaken their stronghold over Punjab’s Gurdwara politics, particularly given their political clout is limited outside Punjab.

The controversy surrounding the authority to amend the 1925 Act points to an urgent need for a reimagined approach to Sikh representation. With the ongoing contention in Punjab, CM Mann’s interventions have stirred up debates that may, in fact, redefine Sikh religious and political identity in the years to come. The hornet’s nest is indeed disturbed, but it could be a catalyst for much-needed change.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Khalsa Vox or its members.