AI Generated Summary

- Led by Sikh religious leader Gurdeep Kaur, the women were not just there to talk about religion but to confront a question that has haunted them for years — how can they stop losing their daughters, not just to another faith but to a way of life that feels alien to their cultural and religious identity.

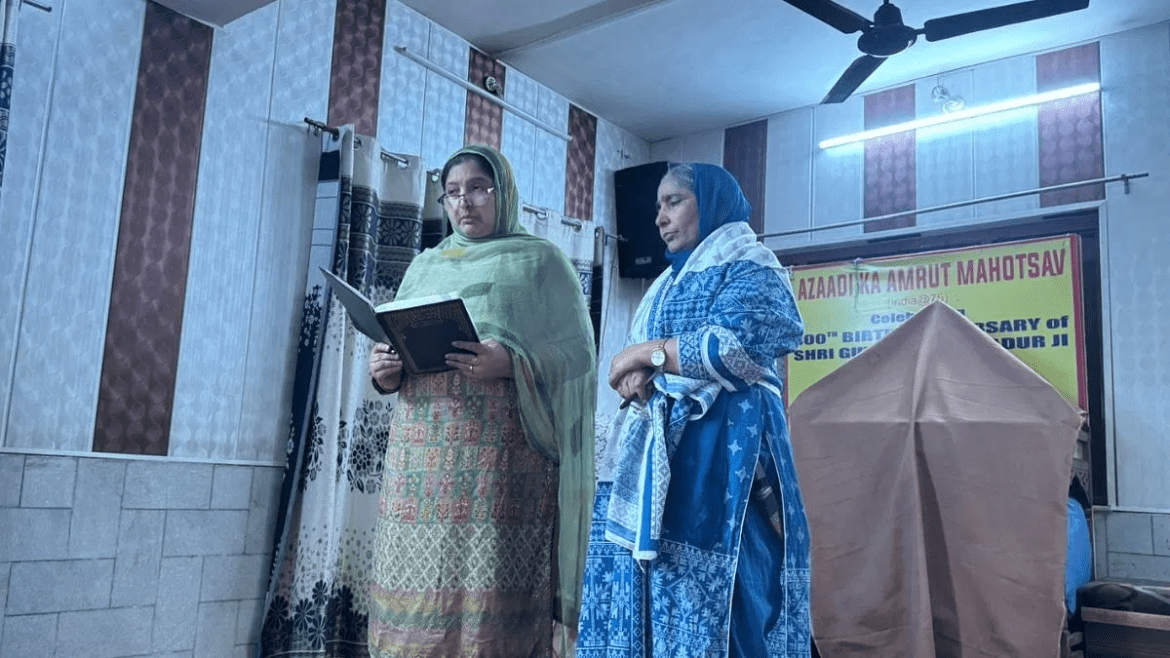

- In the quiet basement of a Gurdwara in the heart of Srinagar, a group of Sikh mothers gathered recently to discuss a growing issue that has shaken their small, tightly-knit community.

- While no one in the Sikh community has openly invoked the term “love jihad,” a loaded phrase frequently used in parts of India to suggest coercive conversion through romance, the fears it stokes have seeped into the discourse.

In the quiet basement of a Gurdwara in the heart of Srinagar, a group of Sikh mothers gathered recently to discuss a growing issue that has shaken their small, tightly-knit community: the conversion of Sikh women to Islam through interfaith marriages. Led by Sikh religious leader Gurdeep Kaur, the women were not just there to talk about religion but to confront a question that has haunted them for years — how can they stop losing their daughters, not just to another faith but to a way of life that feels alien to their cultural and religious identity?

Kaur, 52, underscored the role mothers play in imparting spiritual knowledge to their daughters. “You have failed as a mother if your daughter doesn’t pray,” she stated firmly, imploring those gathered to teach Sikh religious texts and traditions to their children. But her words struck at the heart of a bigger issue in Kashmir’s Sikh community, a micro-minority of about 40,000 people. The concern isn’t just about the conversions; it’s about a larger fear — the potential erasure of their culture and identity within a population that dwarfs them.

This fear intensified after a young Sikh woman’s conversion to Islam recently went viral on social media. In the video, the woman, who now goes by the name Qurat ul Fatima, spoke of a seven-year journey to Islam, describing it as her “original religion.” She claimed she had researched the faith for years before making her decision. Her story has divided opinions, stirring both congratulatory messages from Muslims and sorrowful reactions from Sikhs, who see her conversion as a symbolic loss for their community.

The community’s anxieties over these conversions are deeply tied to Kashmir’s sensitive socio-political landscape. Sikhs in Kashmir have, for decades, carved out a peaceful existence amidst the region’s larger conflicts, choosing to preserve their culture quietly. But these conversions have punctured that peace, adding a new dimension to the inter-community tensions. While no one in the Sikh community has openly invoked the term “love jihad,” a loaded phrase frequently used in parts of India to suggest coercive conversion through romance, the fears it stokes have seeped into the discourse.

Some Sikh community members have spoken candidly about how they find the social media posts celebrating these conversions as “provocative.” Angad Singh, a 28-year-old resident of Srinagar, said that seeing such messages on his Facebook page “stirs emotions” and makes his community feel “marginalized.” To him, these videos and posts seem to flaunt what he feels is the “loss” of Sikh daughters, which resonates among other Sikhs who worry about the community’s fragile demographic presence in the region.

While the viral video generated waves, the Grand Mufti of Jammu and Kashmir, Mufti Nasir-ul-Islam, has expressed clear disapproval of conversions made purely for marriage. He emphasized that conversion should be an informed choice, not a mere formality to satisfy marital or societal pressures. “One should convert only after reading about Islam and being certain that they want to convert,” he said, underlining that true conversions should emerge from spiritual conviction, not convenience.

Yet, for many interfaith couples, love is enough to prompt a conversion, and for some, it’s the only way to navigate societal pressures. The story of Asma (name changed), a Sikh woman who married a Muslim man, encapsulates this struggle. Despite her willingness to embrace her husband’s religion, her relationship with him has come at a high personal cost — the loss of her family and the constant need to assert that her choice was freely made. “I loved him, and that’s why I got married. Religion was never an issue for me,” she shared, revealing the complex emotions and sacrifices that interfaith couples in Kashmir often experience.

Kashmir’s interfaith couples also face the lingering shadow of communal tensions. Some couples, like Asma and her husband, have found acceptance within their new communities but live in constant fear of rejection or worse, violent retribution from their own families. Many, therefore, choose to stay hidden, often relocating to places like Delhi, where they can live openly without fear of societal backlash.

The issue is exacerbated by the rising trend of interfaith relationships among the younger generation, which has begun to test the boundaries of the Sikh community’s traditions. This shift is visible in the quiet migration of some Sikh youths from Kashmir due to limited job opportunities, further weakening the community’s demographic hold in the region.

As Sikh leaders in Kashmir continue to grapple with these changes, their primary strategy has been to reinforce the importance of religious education. They believe that teaching Sikh children about their faith, its values, and traditions is the most effective way to prevent conversions and protect their cultural identity. For these parents, each interfaith marriage feels like a chapter closing on their history in Kashmir, and many now worry about what remains of the small Sikh population if such trends continue.

The challenge facing the Sikh community in Kashmir speaks to a larger struggle many micro-minority communities experience in regions with dominant religious identities. It’s a struggle for visibility, survival, and acceptance, and while love and religion may never fully reconcile in Kashmir, the community’s hope lies in fortifying its identity, one generation at a time.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Khalsa Vox or its members.