AI Generated Summary

- While the government’s directive is being welcomed as a step in the right direction, conservationists argue it comes “too late,” with irreversible damage already done to the sacred precincts of the Golden Temple and the historic walled city.

- From the era of the Sikh Misls (1765–1802), which laid down the city’s foundational neighborhoods or katras, to the golden age under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who fortified its walls and embellished it with gardens, havelis, and forts, Amritsar’s urban identity is woven into its spiritual and cultural tapestry.

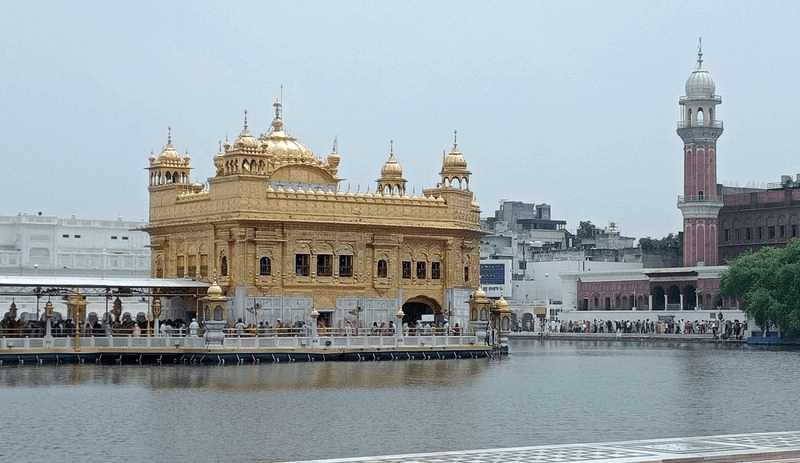

- The Golden Temple is more than a religious landmark — it stands at the heart of a city steeped in centuries of Sikh history.

The Punjab government’s recent move to regulate high-rise constructions around the Golden Temple has reignited debate over the city’s rapidly changing skyline — a transformation many experts see as an erosion of the holy city’s historic soul.

In a communiqué issued last week, Local Bodies Minister Dr. Ravjot Singh called for immediate action against unauthorized constructions marring the skyline around the 450-year-old Sikh shrine. The statement also demanded a report on violations within a week, underscoring the growing concern over urban encroachment on one of India’s most iconic heritage sites.

While the government’s directive is being welcomed as a step in the right direction, conservationists argue it comes “too late,” with irreversible damage already done to the sacred precincts of the Golden Temple and the historic walled city.

A Sacred Skyline Lost

Modern buildings — some towering over the skyline, others encased in glass facades — have sprouted in close proximity to the Golden Temple complex, violating both national and international norms for heritage preservation. Comparisons between centuries-old paintings and contemporary photographs of the shrine starkly reveal the visual dissonance caused by these developments.

“The character of the surroundings has been completely altered,” says Dr. Balvinder Singh, former head of Guru Ram Das School of Planning at Guru Nanak Dev University. “The skyline once reflected the essence of Sikh architecture. Today, incongruent commercial structures have taken over.”

In fact, previous efforts to preserve the area have already fallen short. An overhead water tank that once loomed near the shrine was demolished to restore visual harmony — only for new high-rises to replace it in the following years.

Ignored Guidelines, Missed Warnings

Urban planners and conservationists point out that existing guidelines have long warned against such developments. Chapter 12 of the 1988 National Commission on Urbanisation report outlines key recommendations for preserving historic cityscapes, particularly in areas not built for modern vehicular traffic.

Yet, Amritsar has witnessed a slew of urban projects — from elevated roads to widened boulevards — that have further chipped away at its traditional fabric. “Beautification schemes like the approach road and entrance plaza around the Golden Temple have, ironically, contributed to its cultural disfigurement,” says a local heritage expert.

From Misls to Modern Mayhem

The Golden Temple is more than a religious landmark — it stands at the heart of a city steeped in centuries of Sikh history. From the era of the Sikh Misls (1765–1802), which laid down the city’s foundational neighborhoods or katras, to the golden age under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who fortified its walls and embellished it with gardens, havelis, and forts, Amritsar’s urban identity is woven into its spiritual and cultural tapestry.

But over the years, many of these structures — particularly in areas like Qila Ahluwalia, Katra Dal Singh, and Bagh Ramanand — have been lost to unchecked commercialization. Today, their names live on in addresses and memories, while the buildings themselves have been replaced by concrete blocks and retail outlets.

Even British colonial rule took a toll. Ram Bagh, once a symbol of Mughal-Sikh synthesis in garden design, was renamed Company Bagh and restructured in the name of modernization. “It is rather unfortunate,” wrote Prof. P.C. Khanna, “that the well-knit civic design created by the Maharaja was soon destroyed by the petty bureaucracy and unimaginative engineers of the British.”

The Way Forward

The post-Independence period, especially between 1947 and 2006, is widely considered the most destructive for Amritsar’s architectural heritage. The chaos of Partition and subsequent rebuilding efforts often overlooked preservation in favor of practicality and expansion.

Now, conservationists say it’s not just about preventing further high-rises but also about actively restoring what remains. Areas like Katra Ahluwalia, Chowk Baba Sahib, and Bazar Kesariya still retain glimpses of their original character — open courtyards, narrow alleys, and age-old wells — all of which deserve thoughtful conservation.

Experts are calling for a comprehensive heritage management plan — one that goes beyond regulating height and delves into preserving historical land use, architectural styles, and the intangible cultural heritage that binds the city’s communities to its sacred spaces.

“It’s not just about stopping what’s wrong,” says Dr. Singh, “but about reviving what’s right — before it’s completely lost.”

As the Golden Temple continues to draw millions of pilgrims and tourists each year, the challenge for authorities is clear: to strike a balance between modernization and preservation, between the vertical ambitions of a growing city and the timeless silhouette of a sacred shrine.