AI Generated Summary

- It was viewed as a taveez—a protective charm—ensuring safe passage across the treacherous kala pani, or “black waters,” under the divine guidance of Khwaja Khizar, the Sufi saint believed to watch over travelers.

- According to the English dictionary, a passport is “a document that serves as both an identity card and a travel permit.

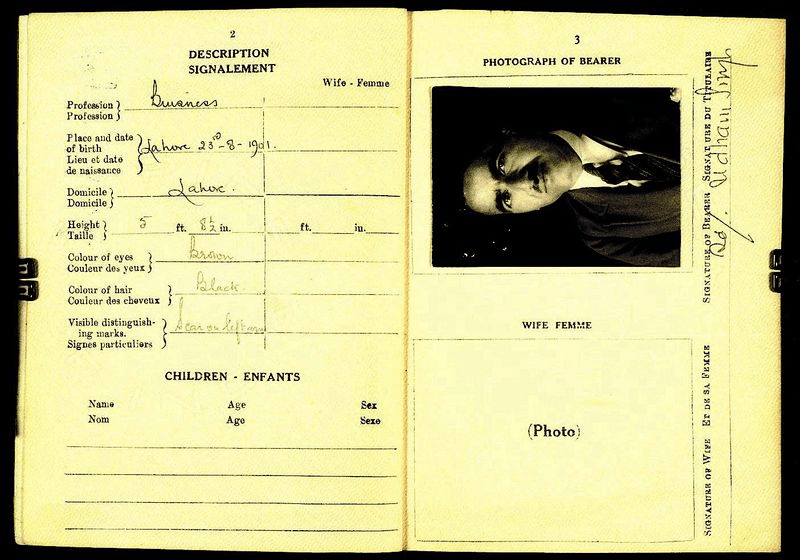

- It bore a photograph and either a signature or a thumbprint of the bearer.

In the modern world, a passport is little more than an official booklet—a blend of identification and permission, letting its bearer cross borders and return home. But in the colonial imagination of Punjab, this unassuming document carried far greater significance. It was not just a travel permit; it was a symbol of freedom, a talisman of protection, and a mythical flying chariot carrying dreams across oceans.

According to the English dictionary, a passport is “a document that serves as both an identity card and a travel permit.” Yet, for generations of Punjabis during the British Raj, the passport held deeper, more mystical meanings. It was viewed as a taveez—a protective charm—ensuring safe passage across the treacherous kala pani, or “black waters,” under the divine guidance of Khwaja Khizar, the Sufi saint believed to watch over travelers. For many, it was an udankhatola, a mythical flying vehicle from Indian folklore, capable of carrying them to distant lands and unknown destinies.

The mystique surrounding the passport was not just spiritual—it was deeply political. In 1915, the British government introduced the mandatory ‘paper passport’ for overseas travel. This policy shift abruptly united various groups of colonial subjects: soldiers bound for war, laborers seeking work in the Americas, and exiled revolutionaries avoiding the imperial net. All were suddenly tethered to a single sheet of paper, no larger than a folded foolscap, that now dictated their right to move across the globe.

This early passport was a bare-bones document. It bore a photograph and either a signature or a thumbprint of the bearer. However, the colonial state’s patriarchal norms were starkly evident—women’s passports carried no photograph. Instead, a handwritten note filled the space: “Lady in Purdah,” reducing female identity to anonymity under a veil.

The design of the passport evolved with time. In 1921, a new version was issued: a 32-page, blue-covered booklet. This marked the birth of the modern Indian passport’s physical form, though its purpose remained steeped in imperial control.

Among the historical relics preserved in the British Library today are the passport photographs of two of Punjab’s most renowned anti-colonial heroes—Ajit Singh and Udham Singh. Both men spent years abroad, navigating a world policed by passports and colonial surveillance. Ajit Singh, uncle to the revolutionary Bhagat Singh, lived in self-imposed exile for over three decades. He managed to secure a Brazilian passport, which allowed him to travel freely in Europe and Latin America. But when he sought to return to India, the British Empire slammed its doors—his Brazilian passport held no sway over their colonial boundaries.

This refusal underscored a brutal irony: the passport, which had come to symbolize movement and autonomy, was also a tool of exclusion and control. For revolutionaries like Ajit Singh and Udham Singh, every journey was both a pursuit of liberation and a confrontation with the limits of imperial power.

In the end, the passport in colonial Punjab was never just a travel document. It was a complex symbol—of aspiration, oppression, protection, and resistance. A simple sheet of paper that could, at once, promise the world and deny it.