AI Generated Summary

- Guru Hargobind, assuming the Guruship at the age of 11 following the execution of the fifth Guru Arjan Dev Ji in Lahore, commenced the construction of Akal Bunga in 1606.

- Guru Hargobind Ji laid the foundation of this structure on an open space across the causeway to Harmandir Sahib, which was originally a mound of soil excavated during the creation of the sarovar.

- These steps, initiated by Guru Hargobind Sahib, such as the wearing of two swords representing Miri-Piri and the establishment of Akal Bunga, marked a significant milestone in the Sikh community’s shift towards a fighting spirit.

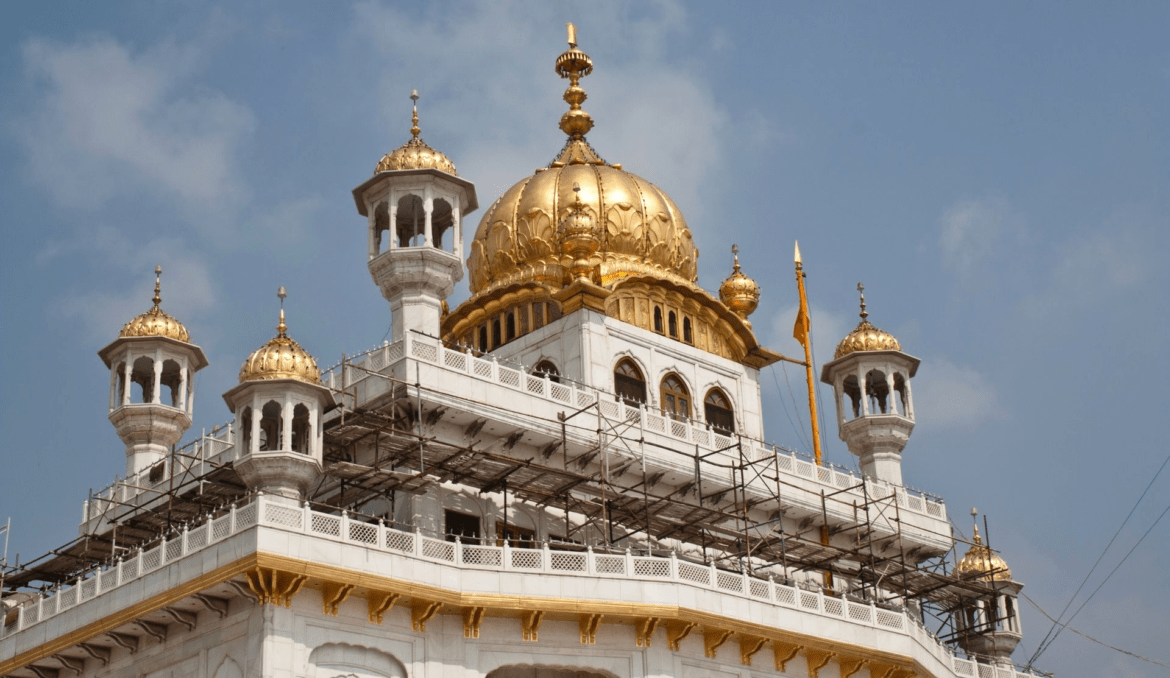

Akal Takht, a five-story building located in front of Sri Harmandir Sahib or Darbar Sahib, has witnessed a remarkable journey from its origins as a memorial lane to its present-day prominence in the emerging digital world. Originally known as ‘Akal Bunga,’ the building was constructed by Guru Hargobind to address the secular aspects of Sikhism. The term “Akal” symbolizes timelessness, while “Takht” translates to “base” and “line” in Persian, also meaning “throne.” Consequently, Harmandir Sahib became the spiritual center of the Sikh faith, while Akal Bunga (later known as Akal Takht) served as the hub of temporal authority. Guru Hargobind introduced the concept of “Miri-Piri,” encompassing both worldly authority and spiritual eminence, to address the secular aspects of Sikhi. Previously, the spiritual authority solely resided in the Guru Granth Sahib, as ordained by Guru Arjan Dev Ji at Harimandir Sahib. It is also known as the Golden Temple due to its gold plating, and its height intentionally remains lower than that of Darbar Sahib as a mark of respect to its spiritual significance.

Guru Hargobind, assuming the Guruship at the age of 11 following the execution of the fifth Guru Arjan Dev Ji in Lahore, commenced the construction of Akal Bunga in 1606. By 1609, the building was completed. Guru Hargobind Ji laid the foundation of this structure on an open space across the causeway to Harmandir Sahib, which was originally a mound of soil excavated during the creation of the sarovar. It was the very site where Guru Hargobind Ji had played as a child. The mound was transformed into an embankment, and a raised platform of bricks was built upon it, serving as Guru Ji’s takht or seat. The raised platform stood at a height of approximately ten to twelve feet and featured two flags representing the temporal and spiritual domains.

Guru Ji’s daily routine involved starting the day with a visit to Harmandir Sahib in the morning for worship, including Aasaa De Vaar, Japji Sahib, and Keertan. In the afternoon, at Akal Bunga, he would meet and engage with those who sought his guidance in resolving their secular affairs or paying their respects. It soon became a preferred option for the resolution of secular matters, eliminating the need to resort to courts in Delhi and Lahore. Guru Ji’s approach to dispute resolution was fair, swift, and impartial. In the evenings, he would return to Harmandir Sahib for prayers and hymn singing. At night, he and his followers would gather at Akal Bunga to listen to martial songs of heroic deeds known as “Dhaddi Waran.”

In front of Akal Bunga, Guru Sahib would hold his darbar, administering justice as a sovereign ruler in court, granting honors or punishments as he deemed fit. He also accepted presents of horses and arms. These steps, initiated by Guru Hargobind Sahib, such as the wearing of two swords representing Miri-Piri and the establishment of Akal Bunga, marked a significant milestone in the Sikh community’s shift towards a fighting spirit. Additionally, the site served as a platform for discussions on issues affecting the Sikhs, including political and military affairs. Ceremonial send-offs of Guru’s envoys and the reception of envoys from other states were also conducted there. Recognizing that the unhindered growth of Sikhism necessitated self-defense, Guru Ji called upon Sikhs to adopt arms for protection. Bards Abdula and Natha were appointed as Dhaddies to recite valorous songs, inspiring the gathered Sikhs. However, following Guru Ji’s prolonged absence from Amritsar and subsequent Gurus’ reduced presence in the city, there was a lull in hukamnammas from Akal Bunga (Takht) between 1615 and 1708, until the death of Guru Gobind Singh.

In 1721, five years after the torture and execution of Banda Bahadur, Akal Takht re-emerged as the epicenter of Sikh affairs. After Banda’s demise, control of Akal Takht was entrusted to the Tat Khalsa. A dispute arose between Bandai Khalsa, the followers of Banda Bahadur, and Tat Khalsa over the control of Akal Takht. Mata Sundri Ji, the wife of Guru Gobind Singh, appointed Bhai Mani Singh as the custodian of Akal Takht and tasked him with resolving the conflict between the two factions. Bhai Mani Singh, after careful deliberation with both groups, passed the Gurmatta to resolve the issue, establishing the tradition of unanimous decision-making. This decision was reached through listening to all parties involved, achieving consensus in accordance with the teachings of Gurbani, and in the presence of Sri Guru Granth Sahib. The procedure for adopting Gurmatta is described by Malcolm in his book “Sikhs Sketch.” The institution of Gurmatta has consistently aided Sikhs in times of calamity, with two annual conclaves held during Diwali and Vaisakhi.

During the Sarbatt Khalsa in 1733, following the rejection of assuming Nawabship by prominent leaders, the position was finally offered to Kapur Singh due to his spirit of service. Initially reluctant to assume a leadership role, Kapur Singh contented himself with being an ordinary Sikh. However, during those challenging times when the very survival of the Sikh community was at stake, a consensus emerged under the guidance of Hukamnamma from Guru Granth Sahib. Kapur Singh was urged to accept this eminent position, marking a turning point for the Sikhs, shifting them from an existential crisis to becoming rulers and masters of their land. Leading the Sikhs with humility and guided by Gurbani and historical insights, Kapur Singh never acted unilaterally but always sought majority consensus, recognizing that a leader’s support stems from the people. His actions and unwavering character as a leader endeared him to the masses. His compassion for the poor and punishment of oppressors further solidified his public standing. He ensured equality and secularism were the guiding principles followed by his associates, never discriminating against anyone based on religion but harshly punishing wrongdoers to serve as a deterrent and foster public confidence. Kapur Singh formed an advisory council comprising ten Sardars, each leading their respective Misls, with the eleventh Singhapuria Misl directly under his command. This structure instilled a democratic and federal system of governance. Despite being the supreme commander, he humbly considered himself as one among the many illustrious sons of the Guru.

In 1756, Ahmed Shah Durrani launched an attack on India, and while returning from Delhi in 1757, his loot was plundered by the Sikhs. In frustration, he ordered the demolition of Akal Takht and Darbar Sahib and filled the sarovar. However, in November 1760, the Sikhs reconvened before Akal Takht, declaring themselves as Sarbatt Khalsa, the Sikh theo-political voice representing the collective consciousness and will of the people. They resolved to seize control of Lahore, the seat of Punjab Government.

Even during Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s rule, the autonomy of the Darbar Sahib Complex, including Akal Takht, was maintained. This arrangement continued during the British Raj from 1850 onwards. However, it broke down during the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919, when the British government attempted to seize control. In response, the Sikhs initiated the Akali movement, demanding the return of control to the democratically elected body of Sikhs known as the Shromani Gurudwara Parbandak Committee (SGPC). The formation of the SGPC introduced a new dynamic to the concept of Sarbatt Khalsa, as the elected body was projected as the representative of the entire Sikh Brotherhood. This revised arrangement transformed the decision-making process within the community and altered the selection of Jathedars.

In the twentieth century, significant changes occurred at the societal level, driven by events such as two World Wars, advancements in transportation modes (such as automobiles, railways, and aircraft), the partition of Punjab during India’s independence in 1947, religious violence, and the migration of Sikh populations from West Punjab to other parts of India. These changes culminated in the formation of the Punjabi Suba and the division of East Punjab into three states. The declaration of Emergency in 1971 and the subsequent migration of Sikhs to Western countries in search of economic opportunities further transformed the distribution of the Sikh population worldwide. Consequently, the SGPC, serving as the representative body of Sikhs and managing historical shrines in Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh, has faced challenges regarding its relevance and authority. The appointment of Jathedars by political party leaders, without grassroots support, has eroded trust in their credibility and the institution itself.

Today, a new set of challenges is emerging, driven by the rapid advancement of technology and the profound impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The internet has transformed the world in the last few decades, and the pandemic has further accelerated changes in the way we work, worship, and engage in communal activities. Lockdowns and travel restrictions have compelled the adoption of virtual events to meet spiritual and emotional needs. Virtual Gurmat Learning Groups, Vichaar webinars, kirtan programs, and Guru Granth Sahib Santhiya classes have proliferated, indicating a new direction for the Sikh community. These nascent efforts hold the potential to unify the faithful on a global scale, transcending geographical boundaries and providing a platform for collective participation and decision-making. The virtual world offers both challenges and opportunities, allowing disillusioned individuals to advocate for reform and reshape the existing arrangements. Virtual gatherings enable the participation of Sikhs from all corners of the world, fostering inclusivity and broader deliberations. Adapting to the new reality requires course correction, drawing inspiration from historical precedents and leveraging the technological advancements of the present era.

Akal Takht stands as a central rallying point for the Sikh community. Aligning with its core values and broader interests, the challenges faced today necessitate reconnecting with this significant institution. By unifying our thoughts, actions, and energies, we can reinforce the impact of our congregational prayers and invoke positive change. The evolving world calls for a renewed focus on the original purpose of Akal Takht and the restoration of its pre-eminent position. As we navigate the path ahead, we must learn from history, embrace the opportunities presented by technology, and strive for a cohesive and inclusive future.