AI Generated Summary

- In view of unrest and protests against this act, the British banned public gatherings but unaware of this order, thousands of unarmed women, children, and men gathered at Jallianwala Bagh that fateful day to celebrate Baisakhi and stage a protest against the arrest of their leaders.

- His diary raises the curtains from his trauma as he remembered the minutest details of his companion and cousin’s death by the bullets, on the spot.

- Mani Ram lost his 13-year-old son Madan Mohan who had gone to this open space in an otherwise cloistered and congested part of the city, along with his friends, as a part of their daily routine.

Under the tyrant’s orders,

An excerpt from ‘Khooni Baisakhi’ by Nanak Singh

they opened fire straight into innocent hearts, my friends.

And fire and fire and fire they did.

Some thousands of bullets were shot, my friends.

Like searing hail they felled our youth

A tempest not seen before, my friends.

On the evening of April 13th, 1919, Hari Ram who was 36 years old, left his house to attend what was supposed to be a ‘peaceful meeting’ against the Rowlett Act. He promised his wife and the mother of his 2 young children that he would be back soon. Ratan Kaur, his wife, had prepared a special rice pudding on the occasion of Baisakhi, the Punjabi New Year and the family was to celebrate together. Hari Ram who was a lawyer, returned home. He kept his promise as most Punjabis do. But his clothes were soaked in blood and his eyes glazed with pain. He had two bullet wounds and died soon after.

The ‘kheer’ remained untouched, untasted.

Ratan Kaur suddenly found herself alone, left to take care of her two kids, aged two and four. She and her family never celebrated Baisakhi after that. Hundreds of families, like hers, were left mourning and shocked at the turn of events. Even though they were not wounded themselves, they were scarred for life.

Dr. Mani Ram lost his 13-year-old son Madan Mohan who had gone to this open space in an otherwise cloistered and congested part of the city, along with his friends, as a part of their daily routine. Little did the parents and children fathom they would never come back. Madan got a bullet in his head, fracturing his skull, and bled to death almost instantly. Mani Ram recalls, “I, with eight or nine others, searched for about half an hour until I could pick out his corpse, as it was mixed up with hundreds of dead bodies lying in heaps.“

Madan Mohan was only one of the many hundreds of people and children who died due to this deeply shameful act of General Dyer.

Lala Guranditta was shot in the leg twice. He recollected the site of cold-blooded genocide to remember hundreds of corpses strewn around in piles, often one atop another. He particularly remembers the body of a twelve-year-old child with a toddler aged around three, their arms tightly clasped around each other, both dead.

Who were these people?

What do we call these deaths, martyrdom or victimhood?

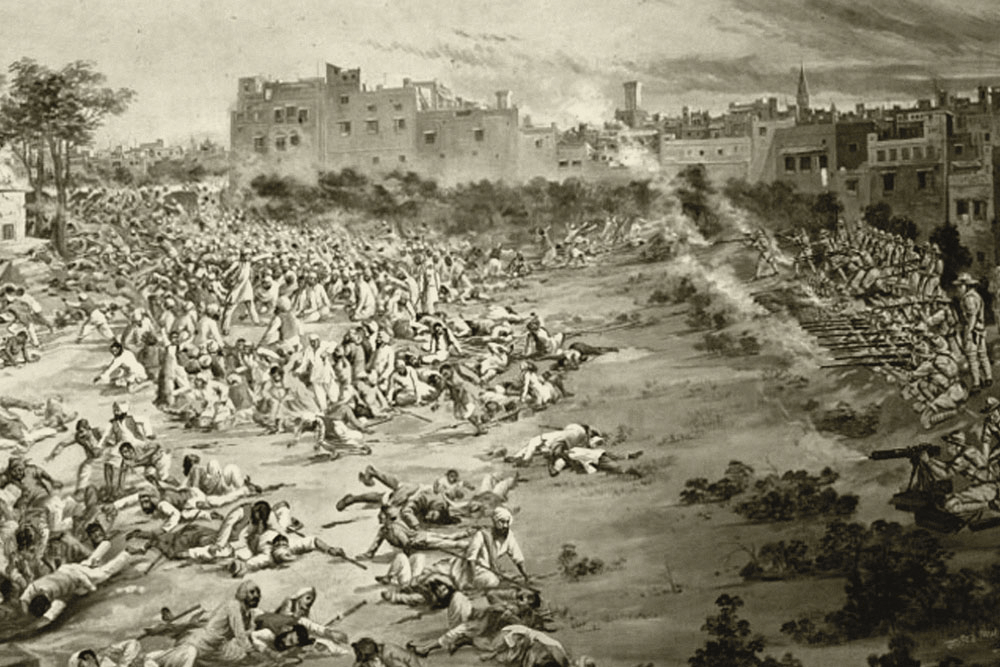

Many lost their lives on this black day in the history of India’s freedom struggle. On April 13th, 1919, there was a call for a peaceful protest against the Rowlett Act. In view of unrest and protests against this act, the British banned public gatherings but unaware of this order, thousands of unarmed women, children, and men gathered at Jallianwala Bagh that fateful day to celebrate Baisakhi and stage a protest against the arrest of their leaders. Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer was enraged at this so-called ‘disobedience’ of civilians and decided to tackle them and punish them his way. The rest as they say is history! The only exit to the ground was sealed. Without warning, the troops started open fire, and over 1650 rounds of bullets were fired at the unarmed, unsuspecting crowd, non-stop for ten minutes. Many jumped into, what is now called the ‘martyrs well’, to save their lives. This bloody carnage left hundreds dead and thousands injured. And these injured martyrs lived on to be haunted by the bloodbath.

To tell of the gory tale.

One such survivor was 17-year-old Jodh Singh who managed to escape death that day but continued to recall how celebrations turned to massacre till the day he died, in 2003. His diary raises the curtains from his trauma as he remembered the minutest details of his companion and cousin’s death by the bullets, on the spot.

Another survivor was Ishwar Das Anand, who was able to avoid the massacre by minutes. He lived with survivor’s guilt for years as he had left the ground for a business deal just minutes before the firing started. He had left his companions at the site asking them to get some sweets for him as well as save his place. As Ishwar heard wailing while passing through the bazaars, he was ordered by the armed police to leave the streets which he did and ran home. His friends were killed in the incident, the guilt of which stayed with him for life.

Twenty-two-year-old Nanak Suri joined the peaceful protest at Jallianwala Bagh on that fateful day. In, what can easily be called one of the worst atrocities of the British Raj, he survived as he was buried under dead bodies and went unnoticed. He went on to write a long, distressing poem about his harrowing experience. The poem was banned by the British in 1920. After 60 long years, it was rediscovered and translated into English by this grandson, Navdeep Suri.

To quench Dyer’s deadly thirst

With streams of blood their own, my friends

Ah! My city mourns with grief today

Happy homes lie shattered because they go

Heads held high offered for sacrifice

For Bharat Mata’s pride and honor, they go.

The Jallianwala Bagh, as it stands today, renovated and rebuilt, is full of throngs of families, friends, and tourists. There is laughter today, and gaiety but amidst all the cheer, one can sense pathos. A chill runs down the spine as one imagines the event of that atrocity more than a hundred years ago. Isn’t it only natural that the head is automatically bowed and eyes fill up with tears and our hearts swell with pride when we think about these common people who deserve to be called Martyrs?

When the fire was opened the whole crowd seemed to sink to the ground… a whole flutter of white garments, with however a spreading out towards the main gateway, and some individuals could be seen climbing the high wall. There was little movement, except for the climbers.

Sergeant Anderson, General Dyer’s personal bodyguard