AI Generated Summary

- ‘Jugni’, the free-spirited Sikhni, dressed to kill in a peacock blue Punjabi suit, hair tied in a plait with a bright pink ‘parandi’ swaying with her ‘morni jaisi chal’.

- She had jumped into the same well, with her children but “like when you put rotis into a tandoor, and if it is too full, the ones near the top, they don’t cook.

- To the horror and dismay of Sikhs and Hindus in the Punjab region, Indian leaders Gandhi and Nehru caved into the demand of Pakistan.

‘Jugni’, the free-spirited Sikhni, dressed to kill in a peacock blue Punjabi suit, hair tied in a plait with a bright pink ‘parandi’ swaying with her ‘morni jaisi chal’. The fire in her eyes, the pride in her gait, the vivaciousness in her demeanor. Not a difficult image to conjure; Jugni, running through mustard fields, her dupatta trailing behind her like a queen’s cloak. Jugni, laughing her bold boisterous laugh as she rides on the swing on the ancient mango tree in her backyard. Jugni, working as hard as her men in the fields, sweat trickling down her forehead. Jugni; an amalgamation of beauty, pride, and honor

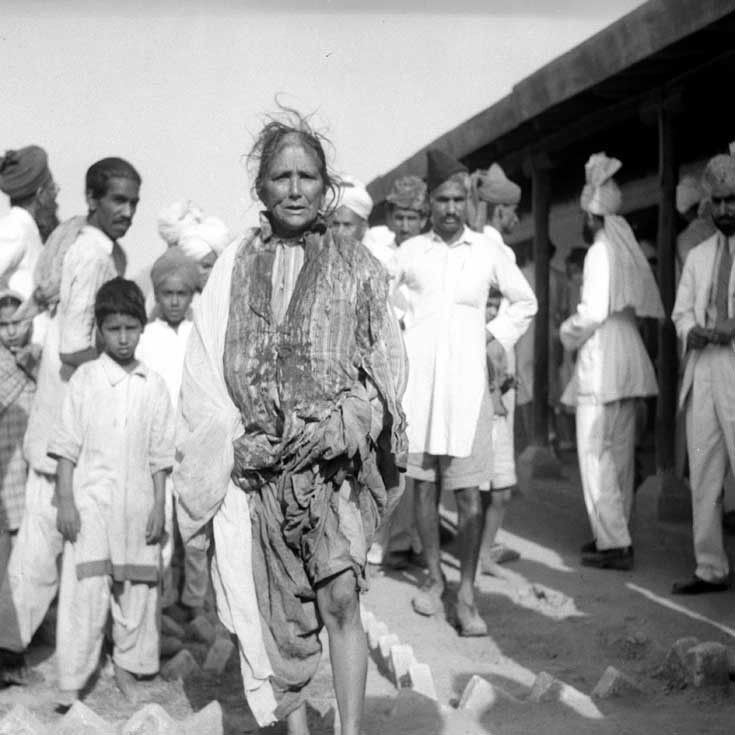

March 8, 1947, saw an unbelievable state of these ‘Jugnis’. ‘The Rape of Rawalpindi’ as it is popularly referred to. Let us start from the beginning; Thoha Khalsa is a village in the Kahuta region of district Rawalpindi, now in Pakistan. This village, till March 1947, was inhabited by flourishing and wealthy Sikh families.

Then, Muslim League demanded the creation of Pakistan, a Muslim nation carved out of India, mutilating Punjab into two halves. To the horror and dismay of Sikhs and Hindus in the Punjab region, Indian leaders Gandhi and Nehru caved into the demand of Pakistan. What followed, as we all are aware, was one of the worst atrocities committed by man against man, but who faced the brunt of this mayhem? Jugni. Woman of Punjab.

There she is. Standing at the ledge of the well at ‘Sardaran di Haveli’. Her eyes shining with pride but there is a lurking sense of doom and helplessness too. Many women, Sikhnis, about a hundred, jumped into that well at Lajwanti’s house that fateful day. Some were even pregnant or with infants in their arms. Don’t you think it requires more than courage to do what they, and many others like them, did? And the men? Many of the Sikh men killed their women and children by their own ‘kirpans’ for the sake of honor. One Sikhni, Sardarni Basant Kaur, lived to tell of the spine-chilling tale. She had jumped into the same well, with her children but “like when you put rotis into a tandoor, and if it is too full, the ones near the top, they don’t cook. They have to be taken out”. So as the well was up to its brim, with bodies; of young women and old, children; both girls and boys, Basant Kaur and her children could not drown. They were pulled out along with the corpses, fortunately or unfortunately, it’s difficult to fathom, for still she is haunted by the sights she saw and challenges she had to face in days to come.

She recounted those horrific stories for her children. A new brutality each day. Rawalpindi and the bloody massacre scarred her for life as she remembered how her husband forced his own nephew to kill him because ‘he did not want to become Mussalman’. Her brothers-in-law butchered their own families to save them from dishonor and ultimately set themselves on fire. An eight-day-old child, an eighty-year-old woman, a man whose knees were swollen, and a girl of eighteen who was pregnant with her first child. All of them died. The Muslims were relentless. They burnt buildings, killed men rampantly, and raped women shamelessly.

Basant Kaur tells of a girl, fifteen years old, who ate opium and died. On the streets. The dogs ate her remains. There was nothing left of her to even perform her last rites. Basant’s own parents, above sixty years of age, were doused with kerosene and set aflame, in the middle of the street, by Muslim mobs. Her sister’s daughters were abducted, ‘one of them was very beautiful’, she remembers. But they were never heard of again. The sister herself pleaded with her father-in-law to behead her, which he did.

Twenty-six girls and women were likewise beheaded that spring, in the village of Thoha Khalsa, all at the hands of their fathers, brothers, and sons or close relatives. Amongst the chanting of ‘ardaas’, the men asking for forgiveness for their actions as their women were martyred.

Undoubtedly, both men and women were victimized and both genders were killed. But life Somehow survives. Just like Sardarni Basant Kaur, Prithpal Singh (who was 11 years old at that time) and Raj Bahadur Singh (16 years old then), still vividly recall that bloody spring, 75 years ago. They retell similar tales of mass suicides and honor killings. Prithpal himself, could not drown in a well and lives to tell stories of at least 200 brave Sikhs who died fighting for valor.

On the 12th and 13th of March, similar, atrocities were witnessed at Choha Khalsa village. Where a Sikh man, Dalip Singh, shot all women in his family and got himself killed, attacking a mob in the local gurudwara. At least 150 Sikhs died in this incident.

The accounts of these genuine tragedies inflicted upon thousands of people who were branded as ‘refugees’ overnight, cannot be overlooked. The ones who lived had demons of their own to fight. Nevertheless, it was the women who carried the burden of ‘honor’ of their families. Their sacrifices are painted in gilded letters of glory, but in retrospect, this ‘mass suicide’ brings an imperative thought to mind. Was the line between choice and coercion blurred? Was it due to a patriarchal consensus imposed upon them? Did they deem their honor towards their community more valuable than their life?

These questions are certainly difficult to answer because most stories are not even properly documented! All we have are a bunch of memoirs of survivors, mostly men who remember these sacrifices of their women with great pride. To the extent of being unaware of their actual feelings.

We, the women of today’s generation, assent to call ourselves ‘feminists. This heart-wrenching gender genocide at Thoha Khalsa manifests gendered violence. It brutally demonstrates how a woman’s sexuality threatens all norms of patriarchy. However, even as a feminist I would not say that all women were “forced” to commit suicide. Those women might have “wanted” to commit Suicide! Because, remember, it’s ‘Jugni’ we talk about. Jugni, as fearless in death as she is in life. Jugni is the epitome of courage and pride. Jugni makes her own decisions.

“The real fear was one of dishonor. If they had been caught by the Muslims, our honor, their honor, would have been sacrificed, lost. It’s a question. of one’s honor… if you have pride, you do not fear.”