AI Generated Summary

- The panoramic view of Lahore, captured in an 1845 painting, vividly depicts the city’s vibrant life, from the mosque of Shah Jahan to the haveli of Sardar Ahluwalia.

- A painting of the Golden Temple of Amritsar by Bishan Singh from the 1870s captures the spiritual and cultural vibrancy of the sacred site.

- In the annals of Indian history, Maharaja Ranjit Singh stands out as a formidable figure who unified the diverse misls of Punjab and established a powerful Sikh empire.

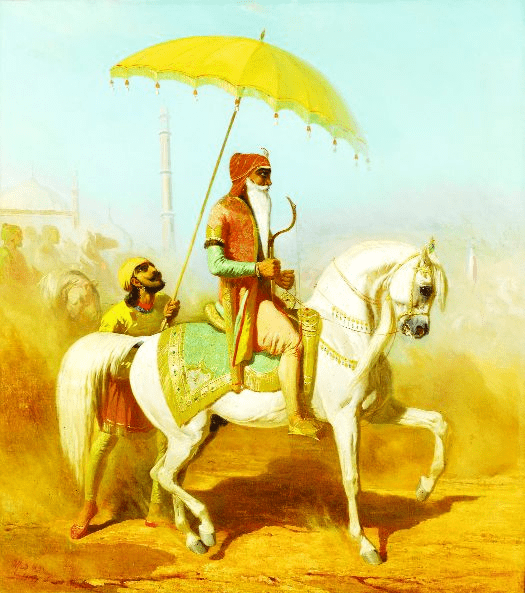

In the annals of Indian history, Maharaja Ranjit Singh stands out as a formidable figure who unified the diverse misls of Punjab and established a powerful Sikh empire. Born in 1780, Ranjit Singh’s meteoric rise began at the tender age of 19 when he conquered Lahore in 1799. Over the next four decades, he not only resisted formidable adversaries such as the Afghans and the British but also left an indelible mark as a warrior, statesman, and monarch. The Wallace Collection in London celebrates this extraordinary legacy through its exhibition, ‘Ranjit Singh — Sikh, Warrior, King,’ co-curated by Dr. Xavier Bray and Sikh art scholar Davinder Toor. This exhibition, which runs until October 20, offers a deep dive into the life and times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, highlighting his multifaceted contributions to the region’s history and culture.

The exhibition is structured into five thematic sections: ‘Prelude to Power,’ ‘Masters of War,’ ‘The Lahore Durbar,’ ‘Firangis,’ and ‘Legacies,’ each meticulously curated to provide a comprehensive understanding of Ranjit Singh’s reign. Scholarly research underscores how his court was a bastion of cosmopolitanism, fostering an ethnically and religiously diverse society. The state’s stability, centralized mechanisms, diligent record-keeping, and strategic management of European incursions are all explored in these sections.

‘Prelude to Power’ sets the stage with a map depicting the expanse of the Sikh empire at the time of Ranjit Singh’s death. This section, rich with paintings from the Toor collection, juxtaposes images of Guru Arjan Dev and Guru Hargobind, illustrating the evolution of the Sikh warrior tradition. As historian Purnima Dhawan notes, this transformation saw ‘sparrows become hawks,’ a metaphor for the rise of the Sikh martial ethos.

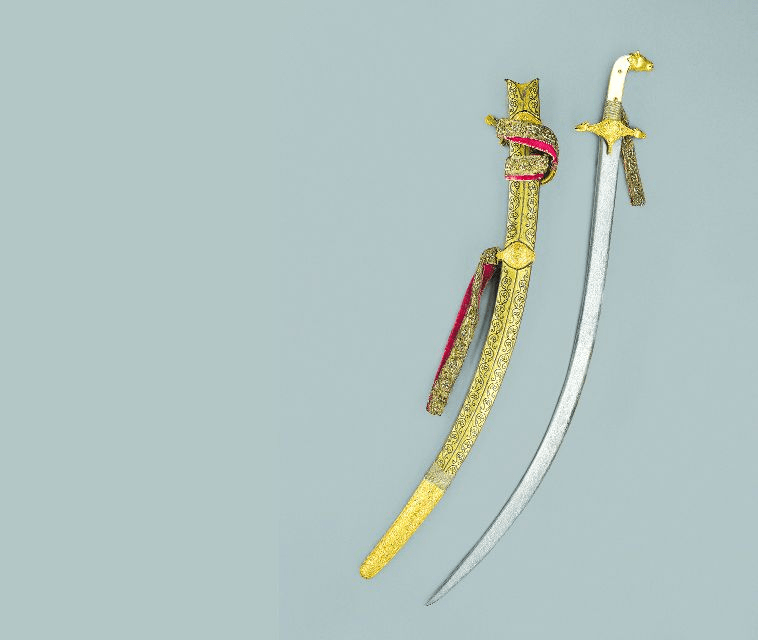

The heart of the exhibition, ‘Masters of War,’ showcases the martial prowess of the Sikhs. This section includes arms, full-body armor, and a dastar bunga, a tall turban worn by the elite Nihangs. Noteworthy is the steel ‘turban helmet,’ which accommodated the Sikh turban and top-knot, signifying the integration of cultural identity with military necessity. This section also highlights Ranjit Singh’s diplomacy, exemplified by his treaty of ‘perpetual friendship’ with the Marathas, a formidable power rivaling the British.

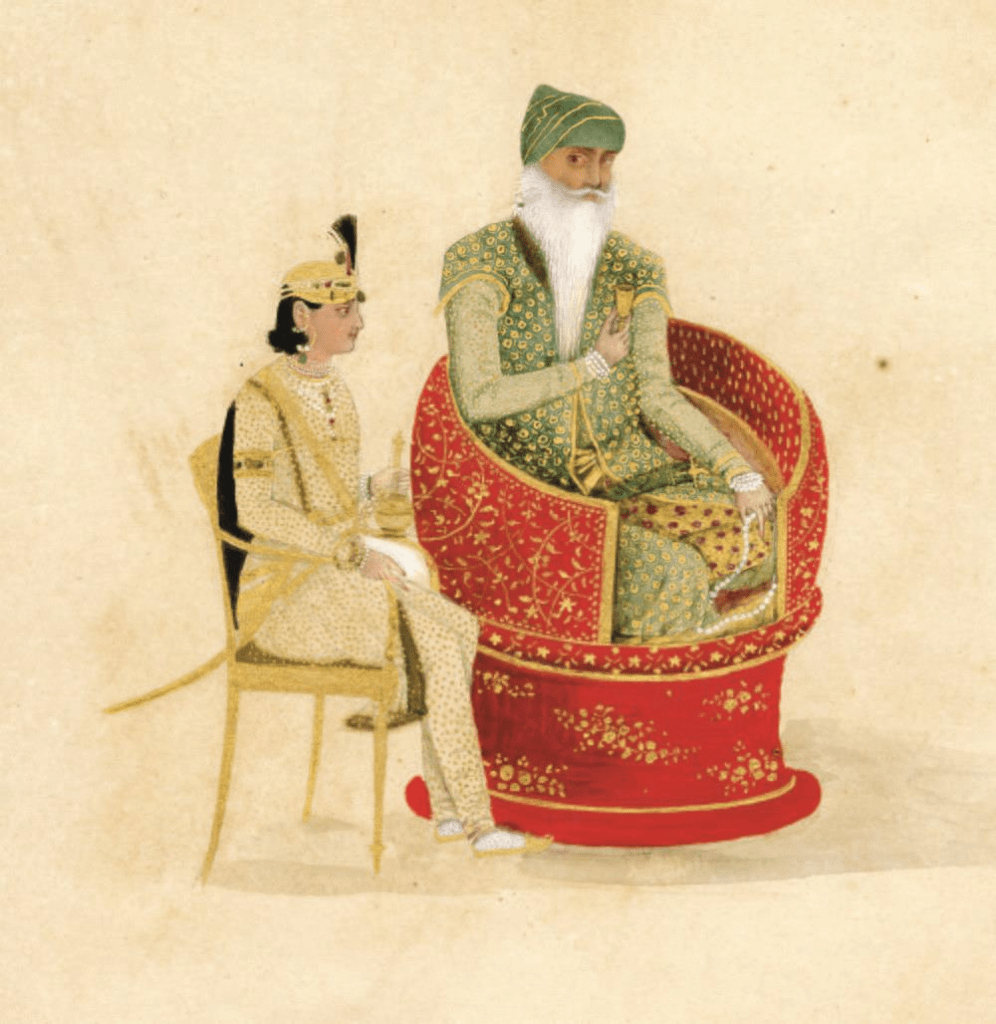

‘The Lahore Durbar’ offers a glimpse into the opulent court of Ranjit Singh through paintings, fabrics, manuscripts, and medals. The centerpiece, the ‘Golden Throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh,’ borrowed from the Victoria and Albert Museum, epitomizes the grandeur of his reign. The panoramic view of Lahore, captured in an 1845 painting, vividly depicts the city’s vibrant life, from the mosque of Shah Jahan to the haveli of Sardar Ahluwalia. Among the fascinating artifacts is the journal of Frances Eden, which includes sketches of the famed Koh-i-Noor diamond, now part of the British royal treasury.

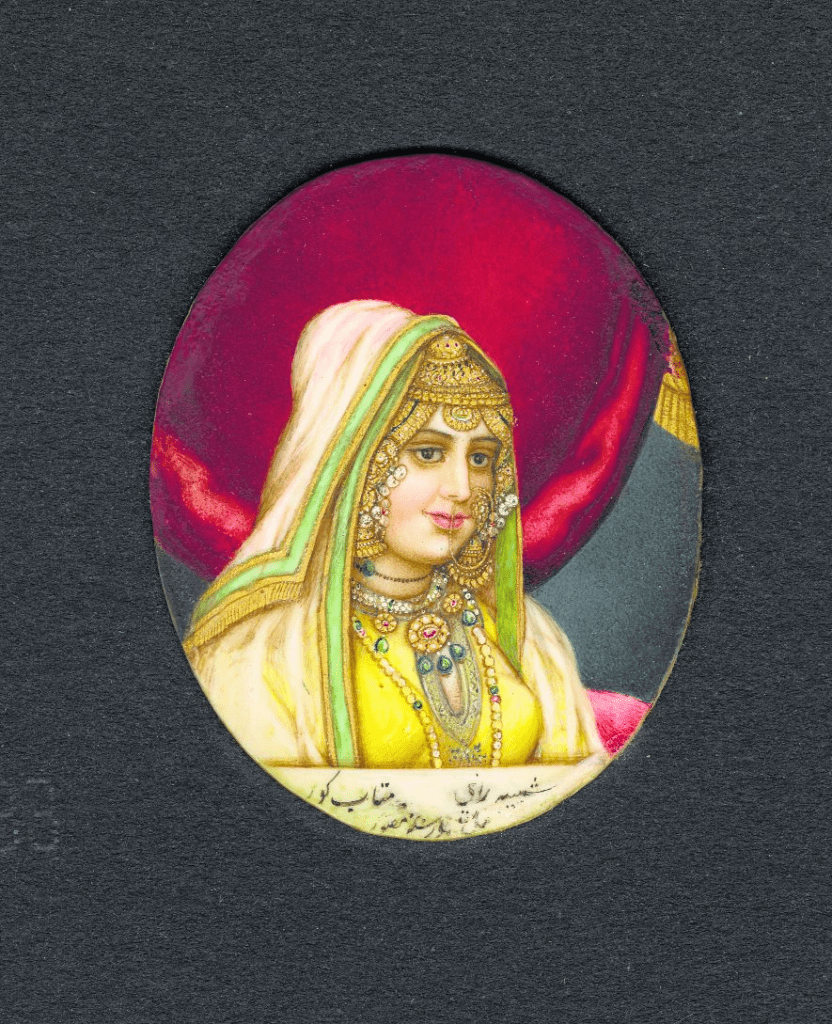

The narrative of Ranjit Singh is incomplete without acknowledging the significant roles played by the women of his court. Recent scholarship by Anshu Malhotra, Priya Atwal, and Radha Kapuria highlights the contributions of these women, from political machinations to everyday interactions. However, the exhibition offers only a limited representation of their impact, primarily through portraits of Rani Mahtab Kaur and Maharani Jind Kaur, the latter’s jewelry providing a glimpse into her life.

A poignant reminder of the historical plunder is visible in the display of Maharani Jind Kaur’s jewels, seized by the British and partially returned after prolonged negotiations. This act of restitution highlights the complex history of colonial acquisitions and the lingering legacy of these artifacts in Western museums.

The section on ‘Firangis’ delves into the interactions between Ranjit Singh and European visitors and officials. It features paintings commissioned by European officers, offering a perspective on how Ranjit Singh was viewed by his contemporaries. An ‘Ornamental Letter of Credence’ from King Louis Philippe I of France underscores the Maharaja’s political significance and the necessity for European powers to forge alliances with him.

The exhibition’s final section, ‘Legacies,’ is particularly evocative. A painting of the Golden Temple of Amritsar by Bishan Singh from the 1870s captures the spiritual and cultural vibrancy of the sacred site. The vivid depiction of pilgrims and the daily life surrounding the temple resonates deeply, evoking a sense of connection to the Sikh heritage.

Despite its comprehensive scope, the exhibition occasionally struggles with accessibility for non-specialists. A timeline of the Sikh empire and key figures would have provided helpful context. Additionally, the lack of translations for non-English materials could render some exhibits incomprehensible to broader audiences.

One of the most compelling pieces in the exhibition is a sword believed to have belonged to Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Adorned with intricate scenes and inscriptions, it symbolizes the fusion of kingship, piety, and martial tradition that defined his reign. The inscription, emphasizing the virtues of feeding and protecting the unfortunate, encapsulates the essence of Ranjit Singh’s legacy.

The exhibition at the Wallace Collection is a significant endeavor, bringing the achievements of Maharaja Ranjit Singh to a global audience. While it predominantly caters to those familiar with Sikh history, it offers a rich tapestry of artifacts and narratives that illuminate the life of one of India’s most remarkable rulers. Through this exhibition, visitors can appreciate the enduring impact of Ranjit Singh’s reign and the vibrant cultural heritage of the Sikh empire.